|

|

|

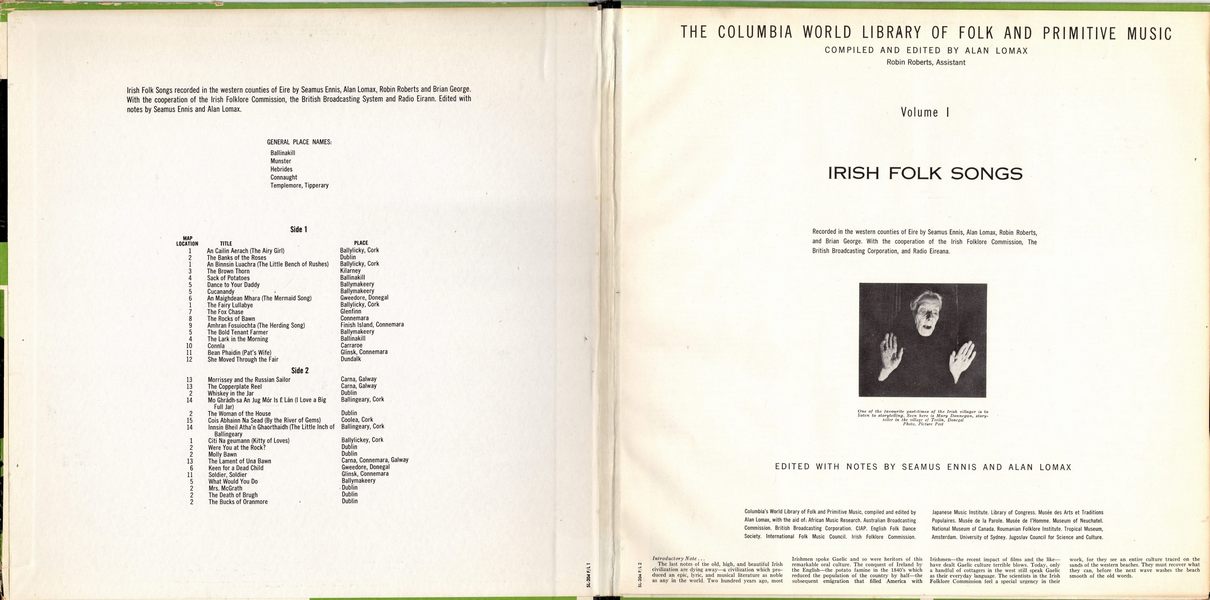

Introductory Note …

The last notes of the old, high, and beautiful Irish civilization are dying away — a civilization which produced an epic, lyric, and musical literature as noble as any in the world. Two hundred years ago, most Irishmen spoke Gaelic and so were heritors of this remarkable oral culture. The conquest of Ireland by the English — the potato famine in the 1840's which reduced the population of the country by half — the subsequent emigration that filled America with Irishmen — the recent impact of films and the like — have dealt Gaelic culture terrible blows. Today, only a handful of cottagers in the west still speak Gaelic as their everyday language. The scientists in the Irish Folklore Commission feel a special urgency in their work, for they see an entire culture traced on the sands of the western beaches. They must recover what they can, before the next wave washes the beach smooth of the old words.

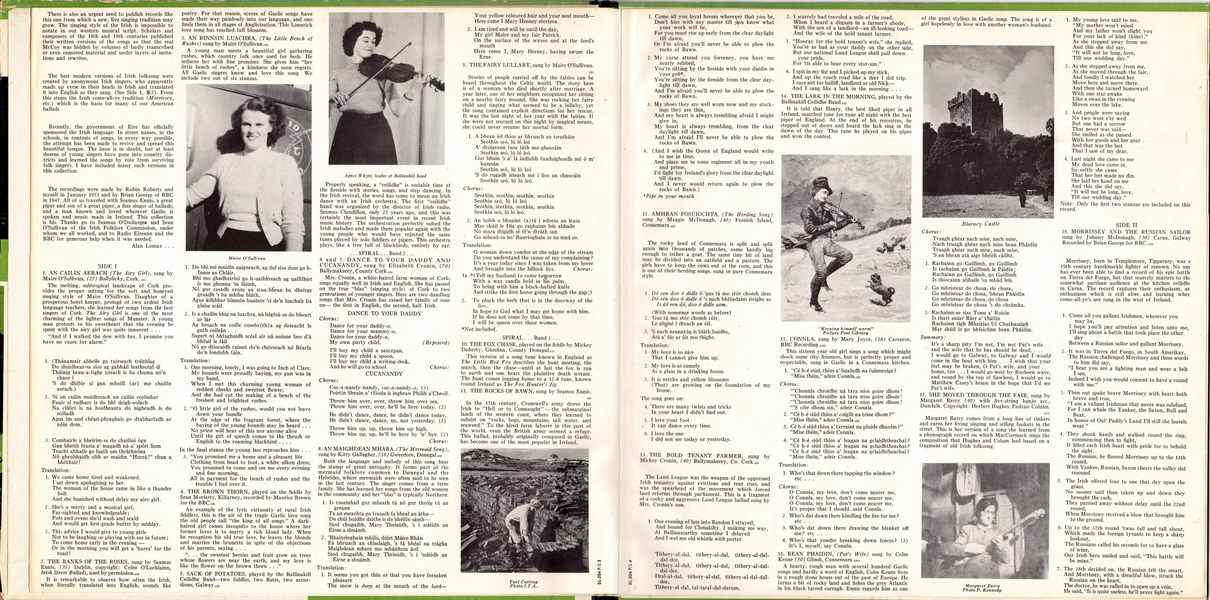

There is also an urgent need to publish records like this one from which a new, live singing tradition may grow. The singing style of the Irish is impossible to notate in our western musical script. Scholars and composers of the 18th and 19th centuries published their written versions of the songs so that the real McCoy was hidden by volumes of badly transcribed or even censored material and under layers of imitations and rewrites.

The best modern versions of Irish folksong were created by anonymous Irish singers, who apparently made up verse in their heads in Irish and translated it into English as they sang. (See Side 1, #2). From this stems the Irish come-all-ye tradition (Morrissey, etc.) which is the basis for many of our American ballads. Recently, the government of Eire has officially sponsored the Irish language. In street names, in the schools, in contests of songs, in every way possible, the attempt has been made to revive and spread this beautiful tongue. The issue is in doubt, but at least dozens of young singers have gone into country districts and learned the songs by rote from surviving folk singers. I have included many such versions in this collection.

The recordings were made by Robin Roberts and myself in January 1951 and by Brian George of BBC in 1947. All of us traveled with Seamus Ennis, a great piper and son of a great piper, a fine singer of ballads, and a man known and loved wherever Gaelic is spoken and music made in Ireland. This collection is his. Thanks go to Seamus O'Duilargea and Seán O'SuIlivan of the Irish Folklore Commission, under whom we all worked, and to Radio Eireann and the BBC for generous help when it was needed.

Alan Lomax …

1. An Cailin Aerach (The Airy Girl), sung by Maire O'Sullivan, (25), Ballylicky, Cork.

The melting, subtropical landscape of Cork provides the proper setting for the soft and honeyed singing style of Maire O'Sullivan. Daughter of a prosperous hotel keeper, protege of two ardent Irish language teachers, she learned her songs from the best singers of Cork. The Airy Girl is one of the most charming of the lighter songs of Munster. A young man protests to his sweetheart that the evening he spent with the airy girl was quite innocent …

"And if I walked the dew with her, I promise you have no cause for alarm."

2. The Banks Of The Roses, sung by Seamus Ennis, (35), Dublin, copyright: Colm O'Lochlainn, Irish Street Ballads, used by permission.

It is remarkable to observe how often the Irish, when literally translated into English, sounds like poetry. For that reason, scores of Gaelic songs have made their way painlessly into our language, and one finds them in all stages of Anglicization. This Limerick love song has reached full blossom.

3. An Binnsin Luachra, (The Little Bench of Rushes), sung by Maire O'Sullivan.

A young man meets a beautiful girl gathering rushes, which country folk once used for beds. He seduces her with fine promises. She gives him "her little bench of rushes", a kindness she soon regrets. All Gaelic singers know and love this song. We include two out of six stanzas.

4. The Brown Thorn, played on the fiddle by Seán Moriarty, Killarney, recorded by Maurice Brown for the BBC.

An example of the lyric virtuosity of rural Irish fiddlers, this is the air of the tragic Gaelic love song the old people call "the king of all songs." A darkhaired girl comes incognito to the house where her former lover is to marry a rich blond lady. When he recognizes his old true love, he leaves the blonde and marries the brunette in spite of the objections of his parents, saying …

" … the sweetest berries and fruit grow on trees whose flowers are near the earth, and my love is like the flower on the brown thorn … "

5. Sack Of Potatoes, played by the Ballinakill Ceilidhe Band—two fiddles, two flutes, two accordions, Galway.

Properly speaking, a "ceilidhe" is sociable time at the fireside with stories, songs, and step dancing. In the Irish revival, the word has come to mean an Irish dance with an Irish orchestra. The first "ceilidhe" band was organized by the director of Irish radio, Seamus Clandillon, only 25 years ago, and this was certainly the most important event in recent Irish music history. The orchestration perfectly suited the Irish melodies and made them popular again with the young people who would have rejected the same tunes played by solo fiddlers or pipers. This orchestra plays, like a tree full of blackbirds, entirely by ear.

6 & 7. Dance To Your Daddy & Cucanandy, sung by Elizabeth Cronin, (70), Ballymakeery, County Cork.

Mrs. Cronin, a white-haired farm woman of Cork; sings equally well in Irish and English. She has passed on the true "blas" (singing style), of Cork to two generations of younger singers. Here are two dandling songs that Mrs. Cronin has raised her family of sons on— the first in English, the second, half Irish.

8. An Maighdean Mhara, (The Mermaid Song), sung by Kitty Gallagher, (18), Gweedore, Donegal.

Both the language and melody of this song bear the stamp of great antiquity. It forms part of the mermaid folklore common to Donegal and the Hebrides, where mermaids were often said to be seen in the last century. The singer comes from a farm family. She has learned her songs from the old women in the community and her "blas" is typically Northern.

9. The Fairy Lullaby, sung by Maire O'Sullivan.

Stories of people carried off by the fairies can be heard throughout the Celtic world. The story here is of a woman who died shortly after marriage. A year later, one of her neighbors recognized her sitting on a nearby fairy mound. She was rocking her fairy child and singing what seemed to be a lullaby, yet the song contained explicit directions for her rescue. It was the last night of her year with the fairies. If she were not rescued on this night by magical means, she could never resume her mortal form.

10. The Fox Chase, played on the fiddle by Mickey Doherty, Glenfinn, County Donegal.

This version of a song tune known in England as The Little Red Fox describes the hunt meeting, the search, then the chase— until at last the fox is run to earth and one hears the plaintive death scream. The hunt comes jogging home to a 12-8 tune, known round Ireland as The Fox Hunter's Jig.

11. The Rocks Of Bawn, sung by Seamus Ennis.

In the 17th century, Cromwell's army drove the Irish to "Hell or to Connaught" — the submarginal lands of the western coast, where they learned to subsist on "rocks, bogs, mountains, salt water, and seaweed." To the hired farm laborer in this part of the world, even the British army seemed a refuge. This ballad, probably originally composed in Gaelic, has become one of the most popular in Ireland.

12. Amhran Fosuiochta, (The Herding Song), sung by Maggie McDonagh, (40), Feenish Island, Connemara.

The rocky land of Connemara is split and split again into thousands of patches, some hardly big enough to tether a goat. The same tiny bit of land may be divided into an oatfield and a pasture. The girls have to keep the cows out of the corn, and this is one of their herding songs, sung in pure Connemara style.

13. The Bold Tenant Farmer, sung by Mickey Cronin, (40) Ballymakeery, Co.

The Land League was the weapon of the oppressed Irish tenantry against evictions and rent rises, and was the spearhead of the movement which forced land reforms through parliament. This is a fragment of a cocky and aggressive Land League ballad sung by Mrs. Cronin's son.

One evening of late into Bandon I strayed,

And bound for Clonakilty, I making me way,

At Ballinascarthy sometime I delayed

And I wet me old whistle with porter.

14. The Lark In The Morning, played by the Ballinakill Ceilidhe Band.

It is told that Henry, the best liked piper in all Ireland, matched tune for tune all night with the best piper of England. At the end of his resources, he stepped out of doors and heard the lark sing in the dawn of the day. This tune he played on his pipes and won the contest.

15. Connla, sung by Mary Joyce, (16), Carraroe, BBC Recording.

This sixteen year old girl sings a song which might shock some city listeners, but is perfectly proper and respectable, sung in Gaelic in a Connemara kitchen.

16. Bean Phaidin, (Pat's Wife), sung by Colm Keane (50), Glinsk, Connemara.

A hearty, rough man with several hundred Gaelic songs and hardly a word of English, Colm Keane lives in a rough stone house out of the past of Europe. He farms a bit of rocky land and fishes the grey Atlantic in his black tarred curragh. Ennis regards him as bne of the great stylists in Gaelic song. The song is of a girl hopelessly in love with another woman's husband.

17. She Moved Through The Fair, sung by Margaret Barry (40), with five-string banjo acc., Dundalk. Copyright: Herbert Hughes, Padraic Coluim.

Margaret Barry comes from a long line of tinkers and earns her living singing and selling baskets in the street. This is her version of a song she learned from a phonograph record on which MacCormack sings the composition that Hughes and Colum had based on a fragment of old Irish folksong.

18. Morrissey And The Russian Sailor sung by Johnny McDonagh, (30), Carna, Galway Recorded by Brian George for BBC.

Morrissey, born in Templemore, Tipperary, was a 19th century bareknuckle fighter of renown. No one has ever been able to find a record of his epic battle on Tierra del Fuego, but that scarcely matters to the somewhat partisan audience at the kitchen ceilidhe in Carna. The record captures their enthusiasm, ar enthusiasm which is still alive and burning wher. come-all-ye's are sung in the west of Ireland.

19. The Copperplate Reel, danced by Steven Folan to tin whistle of Seamus Ennis, Carna, Galway, BBC recording.

When the foregoing ballad was finished, Folan, the step dancer, began to jig. In typical Irish style, he held the upper part of his body stiff; his arms hung loosely by his sides; the activity was from the knees down— for Stephen's feet were playing the tune on the kitchen floor. This is a version of the Scots Cabar Feidh Reel.

20. Whiskey In The Jar, sung by Seamus Ennis, Dublin. Copyright: Colm O'Lochlainn, Irish Street Ballads, sung by permission.

This song recalls the period when it was difficult to tell the difference between a highwayman and a hot-blooded and patriotic Irish rebel forced to take to the hills by the English. Certainly this is one of the finest outlaw ballads in our language.

21. Mo Ghrádh-Sa An Jug Mór Is É Lán, (I Love a Big Full Jug), sung by Kate Moynihan, (25), Ballingeary, Cork, BBC recording.

Irish bards from the time of the epics until today have celebrated the pleasures and glories of the bottle. Such is the theme of this "big song" sung by Kate Moynihan, held by some to be the finest Irish singer of this generation. The "big song" is characterized by its complex stanza structure, its internal rhymes, and its extended legato melody.

22. The Woman Of The House, played on the Uileann Pipes by Seamus Ennis.

The Uileann (elbow), pipes are essentially an indoor instrument. Blown by small elbow bellows, they include the two-octave chanter (melody pipe), — three drones (tenor, middle, and base), at intervals of an octave and tuned to the keynote of the set — and three regulators (pipes fitted with brass keys), that provide simple second and fifth harmonies. This form of the pipes dates back to the 17th century, when piping was a noble profession— when a good piper was entertained by the nobility and was expected to know at least a thousand tunes.

23. Cois Abhainn Na Sead, (By the River of Gems), sung by Maire Keohane, (25), Coolea, Cork.

The three songs that follow are all light love songs sung by young women who have learned their "bLas" from the same group of old folk singers in the same area. Mary Keohane is by far the most educated, self-conscious, and impassioned of the singers. She sings an "aisling" (dream), poem in which the bard recounts his meeting with a woman of heavenly beauty, who, at the end of the poem, is discovered to be "troubled Ireland."

24. Innsin Bheil Atha'n Ghaorthaidh, (The Little Inch of Ballingeary), sung by Gubnait Cronin (20), Ballingeary, Cork.

This is one stanza of a long bardic poem set to a Munster melody, The Palantine's Daughter, and recounting a lover's meeting, quarrel, and reconciliation. The singer has twice won first at the national Gaelic festival, in spite of the fact that she speaks little Gaelic.

25. Citi Na gCumann (Kitty of Loves), sung by Maire O'Sullivan (25),.

One of the finest Irish songs in the narrative ballad style, it tells the story of a young man who has failed to reach an agreement with the parents of his beloved over the dowry and is telling his troubles to the world.

26. Molly Bawn, sung by Seamus Ennis.

Known in England and the United States as The Shooting of his Dear, this is a come-all-ye reworking of an ancient folk theme. In the Hebridean version, it is the cruel mother who advises her son to shoot a swan, even though she knows that the swan is his true love.

27. The Lament For Una Bhán, sung by Seam McDonagh, (50), Carna, Connemara, Galway.

In the time of Cromwell's war, Tomas Costello fell hopelessly in love with Una Bhán McDermott. Separated from Tomas by her father, Una died of love, and Tomas, almost crazed by grief, swam each night to the island where she was buried. There he sang his lament over her grave, until at last Una's ghost bade him leave off lamenting, for the song was so sweet that it would not let her rest, Tomas Costello's lament runs to 45 stanzas in some versions and has been called one of the finest love poems in any language. The singer, a fisherman of Carna, is the man Seamus Ennis calls "the most perfect singer I have met in Ireland".

28. Keen For A Dead Child, sung by Kitty Gallagher, (18), Gweedore, Donegal.

The old-fashioned Irish wake perpetuated pagan funeral rituals, such as funeral games and formal lamentations for the dead. Until recent times, skilled old women in Irish country communities still made keens (caoins or laments), for the dead, but this practice was opposed by the church and has now entirely disappeared. Kitty Gallagher learned this fragmentary keen from an old woman of the neighborhood.

29. Were You At The Rock, played on the Uileann pipes by Seamus Ennis.

The original words run … "Were you at the rock ? Or did you see there my love?". The melody was derived from a song which ostensibly speaks of love but actually refers to the 17th century when the penal code outlawed the Catholic Church and the priests had to say mass in hidden places.

30. Soldier, Soldier, sung by Colm Keane, Glinsk, Connemara.

Colm Keane seldom speaks English, but he often sings this familiar English folk song. It has been so "Irished" by Colm's strong Gaelic musical and linguistic accent, that unless you listened closely, you might think it was a Gaelic ditty. No better example could be found of what happens when a song crosses the language barrier from English into Gaelic.

31. What Would You Do, sung by Elizabeth Cronin.

Similar to the mouth music of Scotland, Brittany, etc., this Irish lilt is a song for dancing, where sense is subordinated to rhythm. In Ireland, it is often the old women who know best how to roll the nonsense syllables rapidly off their tongues and improvise new stanzas.

What would you do if you married a soldier?

What would you do but to follow his gun.

What would you do if he died in the ocean?

What would you do but to marry again.

What would you do if the kettle boiled over?

What would you do but to fill it again.

What would you do if the cows ate the clover?

What would I do but to set it again.

Then there is lilting.

32. Mrs. McGrath, sung by Seamus Ennis. Copyright: Colm O'Lochlainn, Irish Street Ballads, sung by permission.

This ballad is a bitter comment on the wars against Napoleon. Then, as now, the chief export of Ireland was its young men, who had to starve at home or become soldiers of fortune. The recruiting sergeant was a dreaded figure in those days, for if you accepted his shilling for a drink, you could be legally pressed into the army.

33. The Death Of Brugh, sung by Johnny McDonagh, Dublin.

There is violent contrast between the gallow's humour of the previous song and the strong sentimentality in this ballad of the Irish Civil War. The song reports an incident in the uprising of 1922, when Cathal Brugh was shot as he tried to escape by the rear door of a Dublin hotel. The tune is an adaptation of the English All Round My Hat I Wear the Green Willow.

34. The Bucks Of Oranmore, played on the Uileann pipes by Seamus Ennis.

This is one of the "big" reels, a test piece for piper, composed of five parts, heavily ornament and full of all the tricks that the old pipers knew cranning, pinching, nipping, shivering, and the staccato playing of quick triplets.