|

|

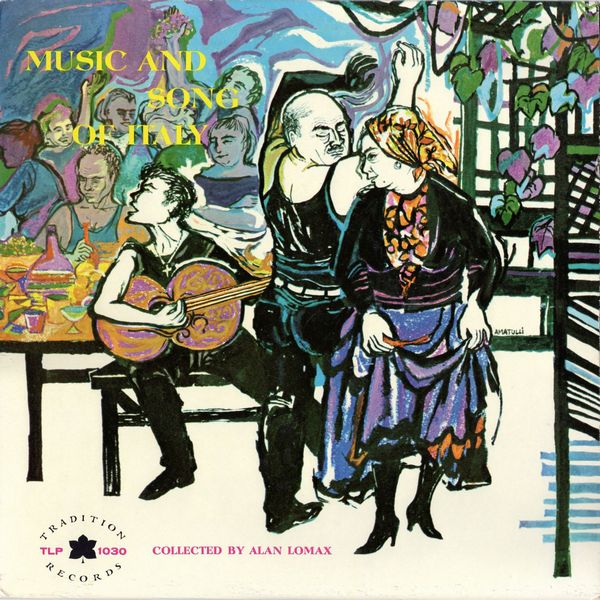

Sleeve Notes

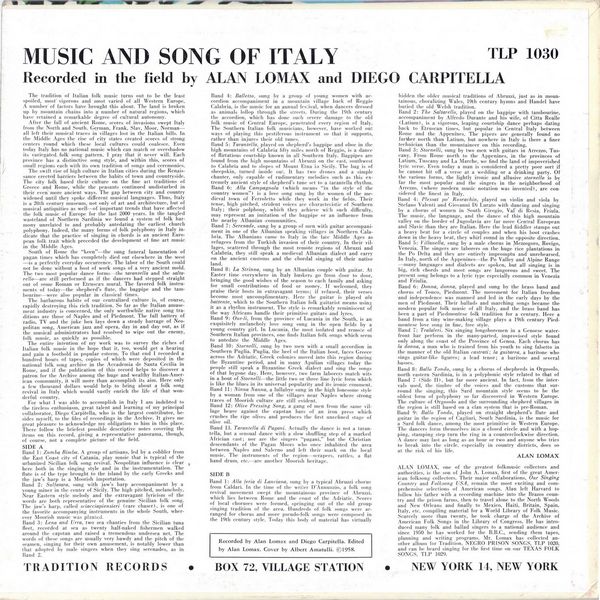

The tradition of Italian folk music turns out to be the least spoiled, most vigorous and most varied of all Western Europe. A number of factors have brought this about. The land is broken up by mountain chains into a number of natural regions, which have retained a remarkable degree of cultural autonomy.

After the fall of ancient Rome, scores of invasions swept Italy from the North and South. German, Frank, Slav, Moor, Norman — all left their musical traces in villages lost in the Italian hills. In the Middle Ages the rise of city states created scores of strong centers round which these local cultures could coalesce. Even today Italy has no national music which can match or overshadow its variegated folk song pattern. I pray that it never will. Each province has a distinctive song style, and within this, scores of small regions each — with its own tradition of songs and ceremonies.

The swift rise of high culture in Italian cities during the Renaissance erected barriers between the habits of town and countryside. The city folk based their culture on the fine art traditions of Greece and Rome, while the peasants continued undisturbed in their even more ancient ways. The gap between city and country widened until they spoke different musical languages. Thus, Italy is a 20th century museum, not only of art and architecture, but of musical antiquities as well—of important trends that have affected the folk music of Europe for the last 2000 years. In the tangled wasteland of Northern Sardinia we found a system of folk harmony unrelated to and probably antedating the earliest church polyphony. Indeed, the many forms of folk polyphony in Italy indicate that the practice of singing in chords is an ancient European folk trait which preceded the development of fine art music in the Middle Ages.

South of Rome the "keen" — the sung funeral lamentation of pagan times which has completely died out elsewhere in the west — is a perfectly everyday occurrence. The labor of the South could not be done without a host of work songs of a very ancient mold. The two most popular dance forms — the 'tarantella and the saltarello — are still performed as if the dancers had stepped straight out of some Roman or Etruscan mural. The favored folk instruments of today — the shepherd's flute, the bagpipe and the tambourine — were also popular in classical times.

The barbarous habits of our centralized culture is, of course, rapidly destroying this rich tradition. So far as the Italian amusement industry is concerned, the only worthwhile native song traditions are those of Naples and of Piedmont. The full battery of radio, TV and the juke box lays down a steady barrage of Neopolitan song, American jazz and opera, day in and day out, as if the musical administrators had resolved to wipe out the enemy, folk music, as quickly as possible.

The entire intention of my work was to survey the riches of Italian folk music in the hope that it, too, would get a hearing and gain a foothold in popular esteem. To that end I recorded a hundred hours of tapes, copies of which were deposited in the national folk song archive in the Accademia de Santa Cecilia in Rome, and if the publication of this record helps to discover a patron for the Archive among the huge and wealthy Italian-American community, it will more than accomplish its aim. Here only a few thousand dollars would help to bring about a folk song revival in Italy which would vastly enrich the life of that wonderful country.

For what I was able to accomplish in Italy I am indebted to the tireless enthusiasm, great talent and learning of my principal collaborator, Diego Carpitella, who is the largest contributor, besides myself, to the files of recordings in the Archive. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge my obligation to him in this place. There follow the briefest possible descriptive notes covering the items on this record, giving a representative panorama, though, of course, not a complete picture of the field.

Zumba Bimba, A group of artisans, led by a cobbler from the East Coast city of Catania, play music that is typical of the urbanized Sicilian folk song revival. Neopolitan influence is clear here both in the singing style and in the instrumentation. The flute is of the type brought to the island by the early Greeks and the jaw's harp is a Moorish importation.

Sulfatara, sung with jaw's harp accompaniment by a young miner in the center of Sicily. The high pitched, melancholy, Near Eastern style melody and the extravagant lyricism of the words are both representative of the genuine Sicilian folk song. The jaw's harp, called sciacciapiensieri (care chaser), is one of the favorite accompanying instruments in the whole South, wherever Moorish music was planted.

Lena and Urra, two sea chanties from the Sicilian tuna fleet, recorded at sea as twenty half-naked fishermen walked around the capstan and raised a tremendous undersea net. The words of these songs are usually very bawdy and the pitch of the seamen, singing for their own amusement, is notably lower than that adopted by male singers when they sing serenades, as in Band 2,

Balletto, sung by a group of young women with accordion accompaniment in a mountain village back of Reggio Calabria, is the music for an annual festival, when dancers dressed as animals lollop through the streets. During the 19th century the accordion, which has done such severe damage to the old folk music of Central Europe, penetrated every region of Italy. The Southern Italian folk musicians, however, have worked out ways of playing this pestiferous instrument so that it supports, rather than injures their old tunes.

Tarantella, played on shepherd's bagpipe and oboe in the high mountains of Calabria fifty miles north of Reggio, is a dance of flirtatious courtship known in all Southern Italy. Bagpipes are found from the high mountains of Abruzzi on the east, southwest to Calabria and to slopes of Mount Etna in Sicily. The bag is of sheepskin, turned inside out. It has two drones and a simple chanter, only capable of rudimentary melodies such as this extremely ancient style of shepherd's tune set to a tarantella rhythm.

Alla Campagnola, (which means "in the style of the country women") is a love song sung by the women of the medieval town of Ferroletto while they work in the fields. Their tense, high pitched, strident voices are characteristic of Southern Italy: their polphony. which they achieve with such difficulty, may represent an imitation of the bagpipe or an influence from the nearby Albanian communities.

Serenade, sung by a group of men with guitar accompaniment in one of the Albanian speaking villages in Northern Calabria. The Albanians came to Italy in the late Middle Ages as refugees from the Turkish invasion of their country. In their villages, scattered through the most remote regions of Abruzzi and Calabria, they still speak a medieval Albanian dialect and carry on the ancient customs and the chordal singing of their native land.

La Strinna, sung by an Albanian couple with guitar. At Easter time everywhere in Italy buskers go from door to door, bringing the good wishes of the season to each family and asking for small contributions of food or money. If welcomed, they praise their hosts in extravagant terms; if refused, their verses become most uncomplimentary. Here the guitar is played a/a battente, which to the Southern Italian folk guitarist means using it as a rhythm instrument. The style is remarkably reminiscent of the way Africans handle their primitive guitars and lyres.

Oue-li, from the province of Lucania in the South, is an exquisitely melancholy love song sung in the open fields by a young country girl. In Lucania, the most isolated and remote of Southern Italian provinces, one finds Italian folk songs which seem to antedate the Middle Ages.

Stornelli, sung by two men with a small accordion in Southern Puglia. Puglia. the heel of the Italian boot, faces Greece across the Adriatic. Greek colonies moved into this region during the Byzantine period, and in many Apulian villages today the people still speak a Byzantine Greek dialect and sing the songs of that bygone day. Here, however, two farm laborers match wits in a bout of Stornelli — the little two or three line lyric form which is like the blues in its universal popularity and its ironic comment.

Ninna Nanna, a lullabye sung in the high lonesome style by a woman from one of the villages near Naples where strong traces of Moorish culture are still evident.

Olive Pressing Song, a gang of men from the same village heave against the capstan bars of an iron press which crushes the ripe olives and produces the first unrefined stage of olive oil.

Tarantella di Pagani, Actually the dance is not a tarantella, but a sensual dance with a slow shuffling step of a marked Africian cast: nor are the singers "pagani," but the Christian descendants of the Pagan Moors who once inhabited the area between Naples and Salerno and left their mark on the local music. The instruments of the region — scrapers, rattles, a flat hand drum. etc. — are another Moorish heritage.

Alla feria di Lanciana, sung by a typical Abruzzi chorus from Caldari. In the time of the writer D'Annunzio, a folk song revival movement swept the mountainous province of Abruzzi, which lies between Rome and the coast of the Adriatic. Scores of local choruses were formed, springing out of the old group singing tradition of the area. Hundreds of folk songs were arranged for chorus and more pseudo-folk songs were composed in the 19th century style. Today this body of material has virtually hidden the older musical traditions of Abruzzi. just as in mountainous, choralizing Wales. 19th century hymns and Handel have buried the old Welsh tradition.

The Saltarello, played on the bagpipe with tambourine, accompaniment by Alfredo Durante and his wife, of Citta Realle (Latium). is a vigorous, leaping courtship dance perhaps dating back to Etruscan times, but popular in Central Italy between Rome and the Appenines. The pipers are generally found no further north than Latium, but nowhere in Italy is there a finer technician than the mountaineer on this recording.

Stornelli, sung by two men with guitars in Arrezzo, Tuscany. From Rome north to the Appenines, in the provinces of Latium, Tuscany and La Marche, we find the land of impoverished lyric verse. Even today a man is considered a pretty poor sort if he cannot hit off a verse at a wedding or a drinking party. Of the various forms, the lightly ironic and allusive stornello is by far the most popular and the singers in the neighborhood of Arrezzo, (where modern music notation was invented), are considered the finest in Italy.

Plessat po' Roseachin, played on violin and viola by Stefano Valenti and Giovanni Di Lurato with dancing and singing by a chorus of women in South Girogio, Val di Resia, Friula. The music, the language, and the dance of this high mountain valley on the border of Jugoslavia are far more Central European and Slavic than they are Italian. Here the lead fiiddler stamps out a heavy beat for a circle of couples and when his boot crashes down in the heavy beat, they whirl round in the opposite direction.

Villanella, sung by a male chorus in Mezzogoro, Rovigo, Venezia. The singers are laborers on the huge rice plantations in the Po Delta and they are entirely impromptu and unrehearsed. In Italy, north of the Appenines — the Po Valley and Alpine Range — many languages and dialects are spoken, but all singing is in big, rich chords and most songs are langorous and sweet. The present song belongs to a lyric type especially common in Venezia and Friulia.

Donna, donna, played and sung by the brass band and chorus of Tonco, Piedmont. The movement for Italian freedom and independence was manned and led in the early days by the men of Piedmont. Their ballads and marching songs became the modern popular folk music of all Italy, and the brass band has been a part of Piedmontese folk tradition for a century. Here a band from a tiny wine-making village plays a 19th century Piedmontese love song in fine, free style.

Tralaleri, Six singing longshoremen in a Genoese waterfront bar perform in the many-parted, improvised style found only along the coast of the Province of Genoa. Each chorus has la donna, a man who is trained from his youth to sing falsetto in the manner of the old Italian castrati; la guitarra, a baritone who sings guitar-like figures; a lead tenor; a baritone and several basses.

Ballo Tondo, sung by a chorus of shepherds in Orgosolo, north eastern Sardinia, is in a polyphonic style related to that of Band 7 (Side II), but far more ancient. In fact, from the intervals used, the timbre of the voices and the customs that surround the singing, this Sard mountain style seems to be the oldest form of polyphony so far discovered in Western Europe. The culture of Orgosolo and the surrounding shepherd villages in the region is still based on a clan system that is pre-Roman.

Ballo Tondo, played on straight shepherd's flute and guitar in the region of Cagliari, South Sardinia, is the music for a Sard folk dance, among the most primitive in Western Europe. The dancers form themselves into a closed circle and with a hopping, stamping step turn the ring in a counterclockwise direction. A dance may last as long as an hour or two and anyone who tries to break into the circle, especially in country districts, does so at the risk of his life.

ALAN LOMAX

ALAN LOMAX, one of the greatest folkmusic collectors and authorities, is the son of John A. Lomax, first of the great American folksong collectors. Their major collaborations, Our Singing Country and Folksong USA, remain the most exciting and comprehensive selections of American songs. Alan left Harvard to follow his father with a recording machine into the Brazos country and the prison farms, then to travel alone to the North Woods and New Orleans and finally to Mexico, Haiti, Britain, Spain, Italy, etc. compiling material for a World Library of Folk Music. Scarcely more than twenty, he took charge of the Archive of American Folk Songs in the Library of Congress. He has introduced many folk and ballad singers to a national audience and since 1950 he has worked for the B.B.C., sending them tapes, planning and writing programs. Mr. Lomax has collected another album for Tradition, NEGRO PRISON SONGS, TLP 1020, and can be heard singing for the first time on our TEXAS FOLK SONGS, TLP 1029.