|

|

Sleeve Notes

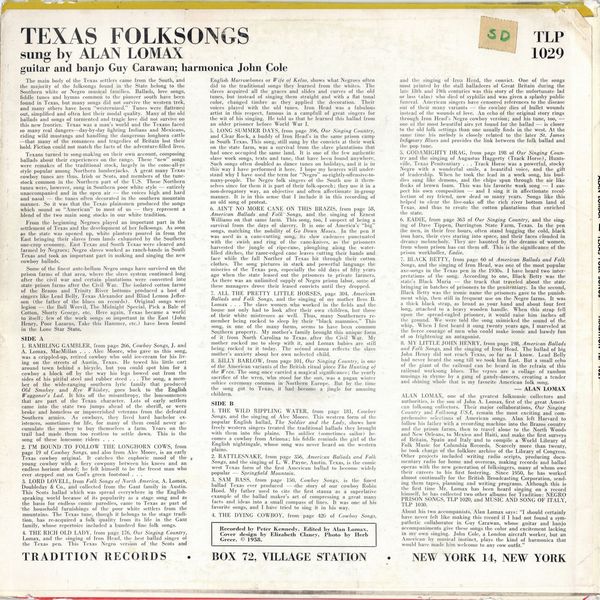

The main body of the Texas settlers came from the South, and the majority of the folksongs found in the State belong to the Southern white or Negro musical families. Ballads, love songs, fiddle tunes and hymns common to the pioneer south have been found in Texas, but many songs did not survive the western trek, and many others have been "westernized." Tunes were flattened out, simplified and often lost their modal quality. Many of the old ballads and songs of tormented and tragic love did not survive on this new frontier. Texas was a man's world and the Texans faced so many real dangers — day-by-day fighting Indians and Mexicans, riding wild mustangs and handling the dangerous longhorn cattle — that many of the romances and tragedies of Britain lost their hold. Fiction could not match the facts of the adventure-filled lives.

Texans turned to song-making on their own account, composing ballads about their experiences on the range. These "new" songs were remakes of the traditional stock, largely in the come-all-ye style popular among Northern lumberjacks. A great many Texas cowboy tunes are thus, Irish or Scots, and members of the tune-stock common in the Northern part of the U.S. These Northern tunes were, however, sung in Southern poor white style — entirely unaccompanied and in the open air — the voices high and hard and nasal — the tunes often decorated in the southern mountain manner. So it was that the Texas plainsmen produced the songs which sound so "American" to most of us — they represent a blend of the two main song stocks in our white tradition.

From the beginning Negroes played an important part in the settlement of Texas and the development of her folksongs. As soon as the state was opened up, white planters poured in from the East bringing their slaves from lands exhausted by the Southern one-crop economy. East Texas and South Texas were cleared and farmed by Negroes; Negro slaves worked as ranch-hands in South Texas and took an important part in making and singing the new cowboy ballads.

Some of the finest ante-bellum Negro songs have survived on the prison farms of that area, where the slave system continued long after the civil war and certain plantations were converted into state prison farms after the Civil War. The isolated cotton farms of the Brazos and Trinity River bottoms produced a host of singers like Lead Belly, Texas Alexander and Blind Lemon Jefferson (the father of the blues on records). Original songs were legion — the Boll Weevil, The Midnight Special, Pick a Bale of Cotton, Shorty George, etc. Here again, Texas became a world to itself; few of the work songs so important in the East (John Henry, Poor Lazarus, Take this Hammer, etc.) have been found in the Lone Star State.

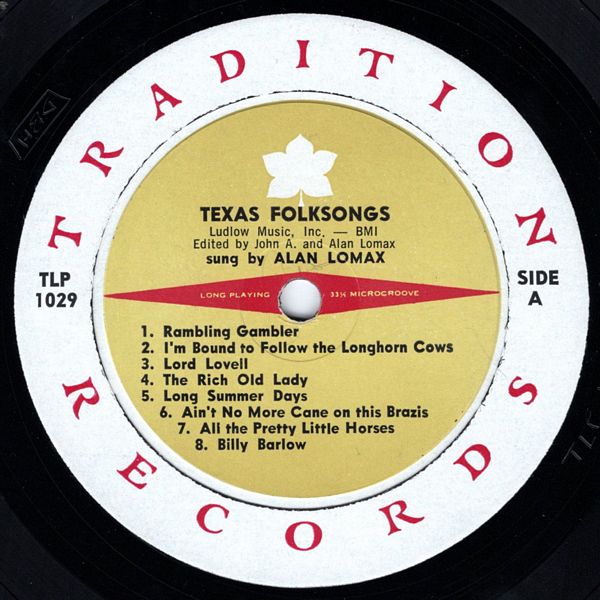

RAMBLING GAMBLER, from page 266, Cowboy Songs, J. and A. Lomax, MacMillan. Alec Moore, who gave us this song, was a crippled-up, retired cowboy who sold ice-cream for his living on the streets of Austin, Texas. He towed his little cart around town behind a bicycle, but you could spot him for a cowboy a block off by the way his legs bowed out from the sides of his pitiful steel and rubber steed . . . The song, a member of the wide-ranging southern lyric family that produced Old Smokey and Rye Whiskey, goes back to the English Waggoner's Lad. It hits off the misanthropy, the lonesomeness that are part of the Texan character. Lots of early settlers came into the state two jumps ahead of the sheriff, or were broke and homeless or impoverished veterans from the defeated Southern armies. As cowboys, they lived hard bachelor existences, sometimes for life, for many of them could never accumulate the money to buy themselves a farm. Years on the trail had made them too restless to settle down. This is the song of these lonesome riders . . .

I'M BOUND TO FOLLOW THE LONGHORN COWS, from page 19 of Cowboy Songs, and also from Alec Moore, is an early Texas cowboy original. It catches the euphoric mood of the young cowboy with a fiery cowpony between his knees and an endless horizon ahead; he felt himself to be the freest man who ever stepped out on God's green footstool . . .

LORD LOVELL, from Folk Songs of North America, A. Lomax, Doubleday & Co., and collected from the Gant family in Austin. This Scots ballad which was spread everywhere in the English- speaking world because of its popularity as a stage song and as the basis for endless comic parodies, came to Texas as part of the household furnishings of the poor white settlers from the mountains. The Texas tune, though it belongs to the stage tradition, has re-acquired a folk quality from its life in the Gant family, whose repertoire included a hundred fine folk songs.

THE RICH OLD LADY, from page 176, Our Singing Country, Lomax, and the singing of Iron Head, the best ballad singer of the Texas pen. This Texas Negro version of the Scots and English Marrowbones or Wife of Kelso, shows what Negroes often did to the traditional songs they learned from the whites. The slaves acquired all the graces and slides and curves of the old tunes, but instead of singing them straight and with a flat tonal color, changed timbre as they applied the decoration. voices played with the old tunes. Iron Head was a fabulous artist in this respect, famous in a campfull of great sing the wit of his singing. He told us that he learned this ballad from an older prisoner before World War I.

LONG SUMMER DAYS, from page 396, Our Singing County, and Clear Rock, a buddy of Iron Head's in the same prison camp in South Texas. This song, still sung by the convicts at their work on the state farm, was a survival from the slave plantations that had once occupied the same land. It is one of the few authentic slave work songs, texts and tune, that have been found anywhere. Such songs often doubled as dance tunes on holidays, and it is in this way 1 have performed it here. I hope my hearers will understand why I have used the term for "Negro' so-rightly-offensive-to-many-people. The Negro folk singers of the South use it themselves since for them it is part of their folk-speech; they use it in a non-derogatory way, an objective and often affectionate in-group manner. It is in this sense that I include it in this recording of an old song of protest.

AIN'T NO MORE CANE ON THIS BRAZIS, from page 58, American Ballads and Folk Songs, and the singing of — Williams on that same farm. This song, too, I suspect of being a survival from the days of slavery. It is one of America's "big" songs, matching the nobility of Go Down Moses. In the pen it was used as a cane-cutting song, its slow cadences punctuated with the swish and ring of the cane-knives, as the prisoners harvested the jungle of ripe-cane, ploughing along the water-filled ditches, the razor-edged cane leaves cutting their hands and face while the fall Norther of Texas bit through their cotton clothes. The song pictures in stark and powerful language the miseries of the Texas pen, especially the old days of fifty years ago when the state leased out the prisoners to private farmers. As there was an unlimited supply of Negro prison labor, some of these managers drove their leased convicts until they dropped.

ALL THE PRETTY LITTLE HORSES, page 304. American Ballads and Folk Songs, and the singing of my mother Lomax . . . The slave women who worked in the fields and the house not only had to look after their own children, but those of their white mistresses as well. Thus, many Southerners remember being rocked to sleep by their "black mammies." This song, in one of the many forms, seems to have been common Southern property. My mother's family brought this unique form of it from North Carolina to Texas after the Civil War. My mother rocked me to sleep with it, and Lomax babies are still being rocked to it today. The second stanza reflects the slave mother's anxiety about her own neglected child.

BILLY BARLOW, from page 101, Our Singing Country, is one of the American variants of the British ritual piece The Hunting of the Wren. The song once carried a magical significance: the yearly sacrifice of the wren, who stood for the sun. was a pagan winter solstice ceremony common in Northern Europe. But by the time the song got to Texas, it had become a jingle for amusing children. SIDE B

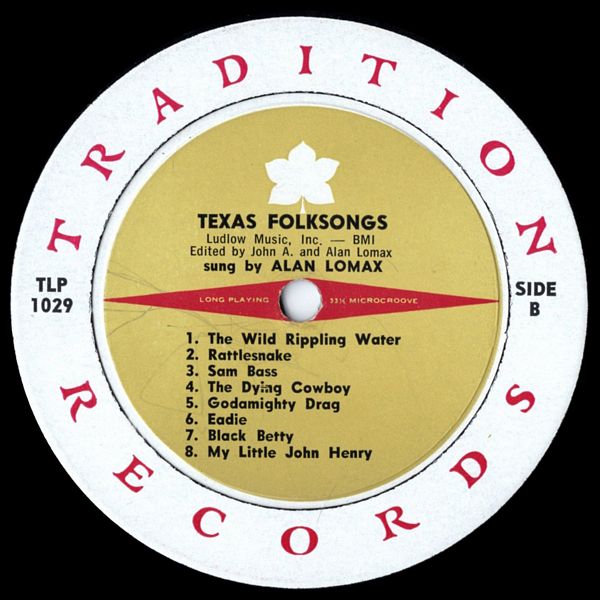

THE WILD RIPPLING WATER, from page 181, Cowboy Songs, and the singing of Alec Moore. This western form of the popular English ballad, The Soldier and the Lady, shows how freely western singers treated the traditional ballads they brought with them into the plains. The soldier (sometimes sailor) comes a cowboy from Arizona; his fiddle reminds the girl of the English nightingale, whose song was never heard on the western plains.

RATTLESNAKE, from page 356, American Ballads and Folk Songs, and the singing of L. W. Payne, Austin. Texas, is the comic west Texas form of the first American ballad to become wide popular — Springfield Mountain.

SAM BASS, from page 150, Cowboy Songs, is the ballad Texas ever produced — the story of our cowboy Hood. My father used to cite the first stanza as a superlative example of the ballad maker's art of compressing a great many facts and ideas into a small compass of lines. It was one of favorite songs, and I have tried to sing it in his way.

THE DYING COWBOY, from page 420 of Cowboy Songs, and the singing of Iron Head, the convict. One of the songs most printed by the stall balladeers of Great Britain during the late 18th and 19th centuries was this story of the unfortunate lad or lass (alas) who died of syphilis and was given a splashy public funeral. American singers have censored references to the disease out of their many variants — the cowboy dies of bullet wounds instead of the wounds of love. An echo of the original story rings through Iron Head's Negro cowboy version; and his tune, too, — one of the most beautiful airs yet found for the ballad — is closer to the old folk settings than one usually finds in the west. At the same time his melody is closely related to the later St. James Infirmary Blues and provides the link between the folk ballad and the pop tune.

GODAMIGHTY DRAG, from page 198 of Our Singing Country and the singing of Augustus Haggerty (Track Horse), Huntsville, Texas Penitentiary . . . Track Horse was a powerful, stocky Negro with a wonderful smile, a beautiful voice, and the gift of leadership. When he took the lead in a work song, his buddies sang like demons, and the chips spun through the air like necks of brown foam. This was his favorite work song — I suspect his own composition — and I sing it in affectionate recollection of my friend, now dead so many years. Songs like this helped to clear the live-oaks off the rich river bottom land of Texas, and thus to create the cotton plantations that enriched the state.

EADIE, from page 363 of Our Singing Country, and the singing of Dave Tippen, Darrington State Farm, Texas. In the pen the men, in their free hours, often stand hugging the cold, black iron bars, their eyes staring into space, and their faces clouded in dreamy melancholy. They are haunted by the dreams of women, from whom prison has cut them off. This is the significance of the prison workholler, Eadie.

BLACK BETTY, from page 60 of American Ballads and Folk Songs, and the singing of Iron Head, was one of the most popular axe-songs in the Texas pen in the 1930s. I have heard two interpretations of the song. According to one, Black Betty was the state's Black Maria — the truck that traveled about the state bringing in batches of prisoners to the penitentiary. In the second, Black Betty was the ironic name the prisoners gave to the punishment whip, then still in frequent use on the Negro farms. It was a thick black strap, as broad as your hand and about four feet long, attached to a heavy wooden handle. When this strap fell upon the spread-eagled prisoner, it would raise him inches off the ground. We were told the song mimicked the sound of the whip. When I first heard it sung twenty years ago, I marveled at the fierce courage of men who could make ironic and bawdy fun of so frightening an antagonist.

MY LITTLE JOHN HENRY, from page 198, American Ballads and Folk Songs, and the singing of Iron Head. The ballad of big John Henry did not reach Texas, so far as I know. Lead Belly had never heard the song till we took him East. But a small echo of the giant of the railroad can be heard in the refrain of this railroad worksong blues. The verses are a collage of random musings in rhyme by a gang of gandy-dancers, creating a tender and shining whole that is my favorite American folk song.

— ALAN LOMAX

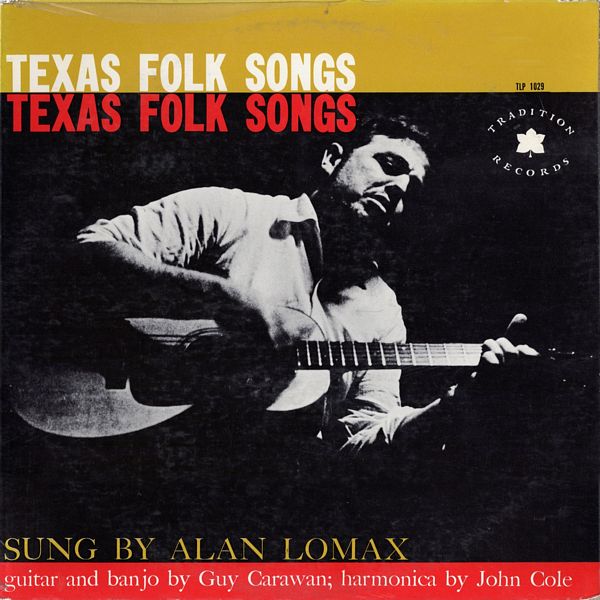

ALAN LOMAX, one of the greatest folkmusic collectors and authorities, is the son of John A. Lomax, first of the great American folksong collectors. Their major collaborations, Our Singing Country and Folksong USA, remain the most exciting and comprehensive selections of American songs. Alan left Harvard to follow his father with a recording machine into the Brazos country and the prison farms, then to travel alone to the North Woods and New Orleans, to Mexico and Haiti, and make the first surveys of Britain, Spain and Italy and to compile a World Library of Folk Music for Columbia Records. Scarcely more than twenty, he took charge of the folklore archive of the Library of Congress. Other projects included writing radio scripts, producing documentary radio for home and overseas, making records and ballad operas with the new generation of folksingers, many of whom owe their careers to his first fostering. Since 1950, he has worked almost continually for the British Broadcasting Corporation, sending them tapes, planning and writing programs. Although this is the first time Mr. Lomax has been heard singing on a record himself, he has collected two other albums for Tradition: NEGRO PRISON SONGS, TLP 1020, and MUSIC AND SONG OF ITALY, TLP 1030.

About his two accompanists, Alan Lomax says: "I should certainly have never felt like making this record if I had not found a sympathetic collaborator in Guy Carawan, whose guitar and banjo accompaniments give these songs the color and excitement lacking in my own singing. John Cole, a London aircraft worker, but an American by musical instinct, plays the kind of harmonica that would have made him welcome to any cow outfit."