|

|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

I was a musician in 1970. At least, that's what I thought. From listening to Bob Dylan's early records, I'd lifted enough guitar riffs, melancholy blues lyrics and Guthrie-type dust bowl stories to make me sound uniquely interesting. What I didn't realise, of course, was that thousands of other seventeen-year-olds around the world were also projecting themselves as tortured "folk" artists.

As a stereotypical young folksinger I was obsessed with the larger-than-life romance of American roots music. And the very idea that Irish folk music could have an equally colourful background was surely absurd. To me, that conjured up visions of tedious coy singalongs about maids wandering around in boreen (whatever they were) or daft parlour ballads involving goats getting into the kitchen of your cottage. Hardly deep stuff, I thought.

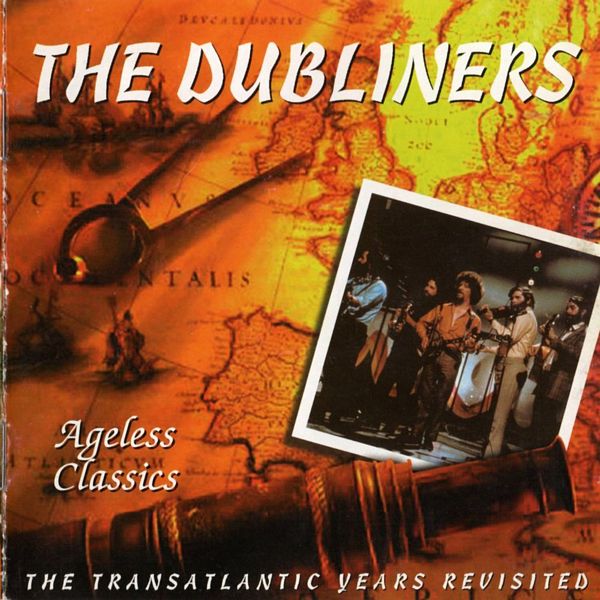

By the time I'd discovered the Dubliners, in that same year, they'd already been on the road for seven years and were a raging success. I could remember seeing them on Top Of The Pops at the time Seven Drunken Nights came out (1967). While amused by the song's double-meaning words, I quickly forgot the Dubliners' music as just a more risque version of Irish traditional.

But when a friend of mine, a tenor banjo player, suggested I listen to some of their records I came to see they were much more than that.

Most of the albums had been recorded in the mid-1960s when the Dubliners' style was at its most raw — and intense. In retrospect, that's what caught my attention. I had decided that I didn't like Irish folk music, but this was far removed from any I'd ever heard before. Those early Transatlantic — label discs, had a kind of spontaneous quality, as if someone had secretly recorded the Dubliners in a country Dublin bar. In other words, they sounded real.

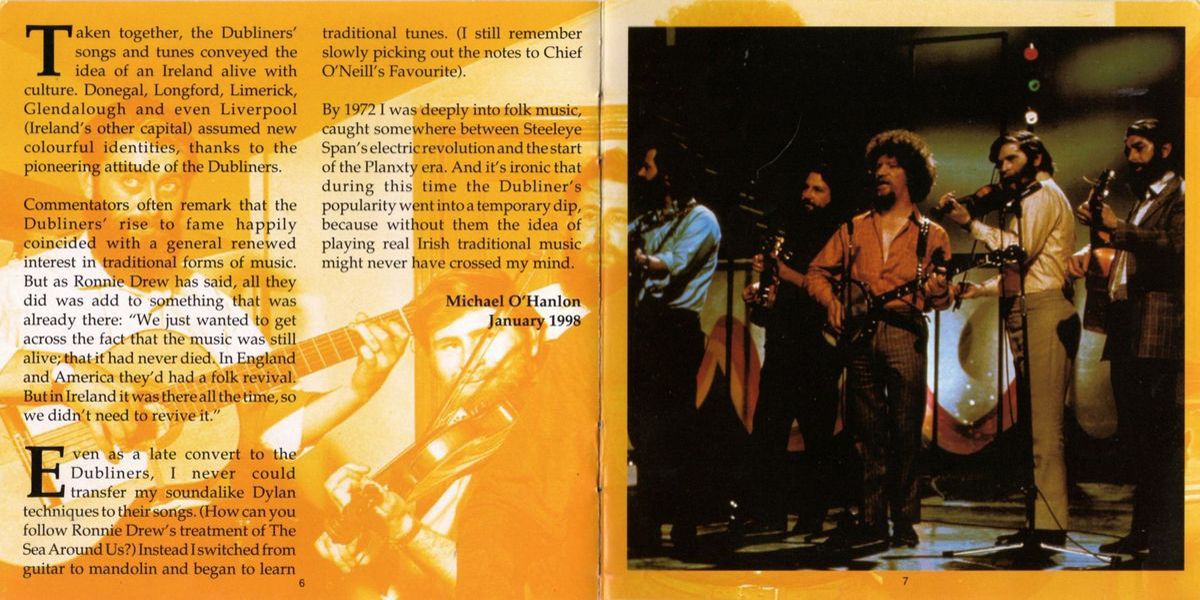

The songs themselves were delivered against a sparse backdrop of acoustic instruments. The combination of guitar, banjos, fiddle and whistle was a rare innovation at the time. The Dubliners were playing Irish music all right, but with all the lift of an Appalachian string band. It was light years away from what I imagined to be folk: the genteel girl singer I accompanying herself on a harp or the monotonous clatter of some ceili band going through the motions.

The Dubliners' sense of humour too was refreshingly satirical — outrageous really for its time. And that kind of coincided with my post-1960s rebellious attitude. Irish politics hadn't yet become a grim taboo subject, and the group could make people laugh at the ridiculous side of conflict. Luke Kelly's entertaining introduction to the live-recorded Nelson's Farewell leads perfectly into the Dubliners' tongue-in-cheek look at how the great man's statue came to grief. The Old Orange Flute too takes an irreverent viewpoint on the then simmering northern "Troubles."

For me, one of the Dubliners' most impressive contributions to folk music was their way of mixing songs and instrumentals on their albums. I'd never really listened to dance tunes before, turned off (like many of my generation) by their "sameness". Barney McKenna, John Sheahan and Ciaran Bourke — the core soloists — changed my attitude dramatically. My banjo-player friend never managed to match McKenna's skill on The Mason's Apron. But we could both marvel at its wild speed, with Barney spurred on by the encouraging shouts of the ecstatic audience. By contrast, Sheahan's understated version of the hornpipe, King Of The Fairies, showed me that you could give old tunes a new rhythm without ruining them.

Taken together, the Dubliners' songs and tunes conveyed the idea of an Ireland alive with culture. Donegal, Longford, Limerick, Glendalough and even Liverpool (Ireland's other capital) assumed new colourful identities, thanks to the pioneering attitude of the Dubliners.

Commentators often remark that the Dubliners' rise to fame happily coincided with a general renewed interest in traditional forms of music. But as Ronnie Drew has said, all they did was add to something that was already there: "We just wanted to get across the fact that the music was still alive; that it had never died. In England and America they'd had a folk revival. But in Ireland it was there all the time, so we didn't need to revive it."

Even as a late convert to the Dubliners, I never could transfer my soundalike Dylan techniques to their songs. (How can you follow Ronnie Drew's treatment of The Sea A round Us?) Instead I switched from guitar to mandolin and began to learn traditional tunes. (I still remember slowly picking out the notes to Chief O'Neill's Favourite).

By 1972 1 was deeply into folk music, caught somewhere between Steeleye Span's electric revolution and the start of the Planxty era. And it's ironic that during this time the Dubliner's popularity went into a temporary dip, because without them the idea of playing real Irish traditional music might never have crossed my mind.

Michael O'Hanlon

January 1998