|

|

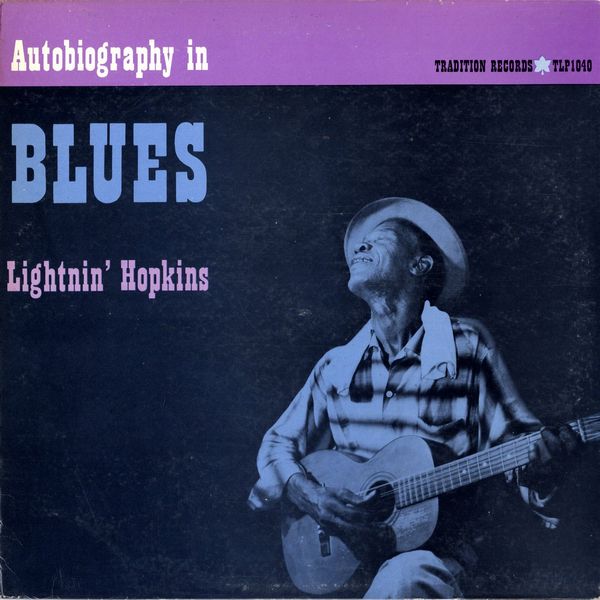

Sleeve Notes

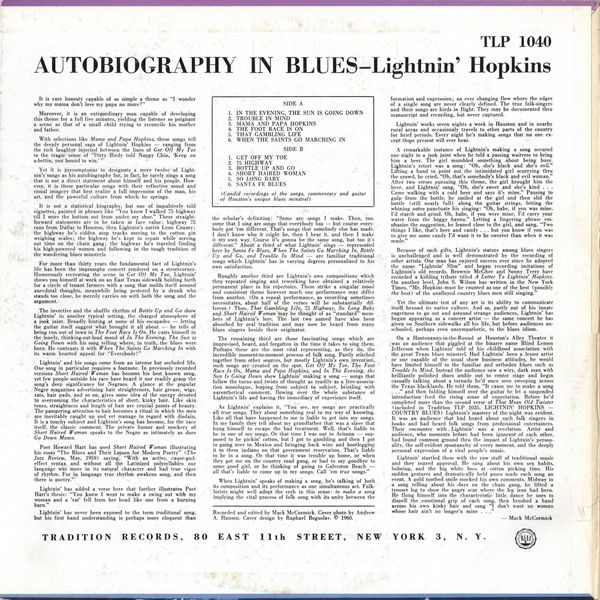

It is rare honesty capable of so simple a theme as "I wonder why my mama don't love my papa no more?"

Moreover, it is an extraordinary man capable of developing this theme for a full five minutes, yielding the listener so poignant a scene as that of a small child trying to reconcile his mother and father.

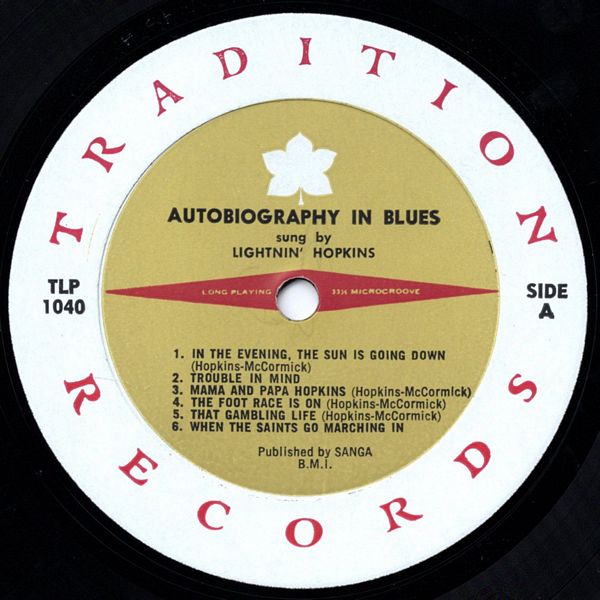

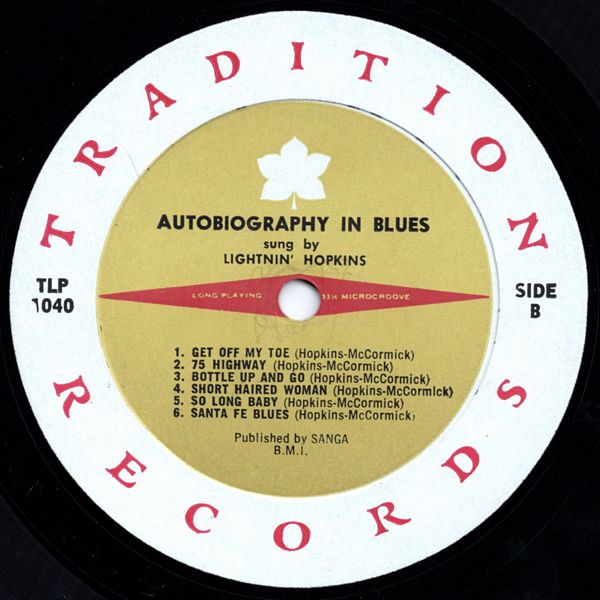

With selections like Mama and Papa Hopkins, these songs tell the deeply personal saga of Lightnin' Hopkins — ranging from the rich laughter injected between the lines of Get Off My Toe to the tragic sense of "Dirty Birdy told Nappy Chin, 'Keep on a-bettin, you bound to win.' "

Yet it is presumptuous to designate a mere twelve of Lightnin's songs as his autobiography for, in fact, he rarely sings a song that is not a direct statement about himself and his people. However, it is these particular songs with their reflective mood and visual imagery that best realize a full impression of the man, his art, and the powerful culture from which he springs.

It is not a statistical biography, but one of impulsively told vignettes, painted in phrases like "You know I walked 75 highway till I wore the bottom out from under my shoe." These straightforward statements are to be taken at face value: highway 75 runs from Dallas to Houston, thru Lightnin's native Leon County; the highway he's ridden atop trucks moving to the cotton gin weighing scales; the highway he's kept in repair while serving out time on the chain gang; the highway he's traveled finding his high-powered women and following in the tough tradition of the wandering blues minstrels.

For more than thirty years the fundamental fact of Lightnin's life has been the impromptu concert rendered on a streetcorner. Humorously recreating the scene in Get Off My Toe, Lightnin' shows you himself at work on an East Texas sidewalk holding forth for a circle of tenant farmers with a song that molds itself around anecdotal thoughts, meanwhile being pestered by a drunk who stands too close, he merrily carries on with both the song and the argument.

The invective and the shuffle rhythm of Bottle Up and Go show Lightnin' in another typical setting, the charged atmosphere of a jook joint. Broadly hinting at some of his escapades — letting the guitar itself suggest what brought it all about — he tells of being run out of town in The Foot Race Is On, He casts himself in the lonely, thinking-out-loud mood of In The Evening, The Sun is Going Down with his song telling where, in truth, the blues were born. He contrasts it with When The Saints Go Marching In with its warm hearted appeal for "Everybody!"

Lightnin' and his songs come from an intense but secluded life. One song in particular requires a footnote. In previously recorded versions Short Haired Woman has become his best known song, yet few people outside his race have heard it nor readily grasp the song's deep significance for Negroes. A glance at the popular Negro magazines advertising hair straighteners, hair grease, wigs, rats, hair pads, and so on, gives some idea of the energy devoted to overcoming the characteristics of short, kinky hair. Like skin tones, straightness and length of hair are crucial points of beauty. The pampering attention to hair becomes a ritual in which the men are inevitably caught up and yet manage to regard with disdain. It is a touchy subject and Lightnin's song has become, for the race itself, the classic comment. The private humor and mockery of Short Haired Woman speaks to the Negro as intimately as does Go Down Moses.

Poet Howard Hart has used Short Haired Woman illustrating his essay "The Blues and Their Lesson for Modern Poetry" (The Jazz Review, May, 1959) saying, "With an active, cause-and-effect syntax and without all the Latinized polysyllables our language was more in its natural character and had true vigor of rhythm. For in language true rhythm awakens song, and then there is poetry."

Lightnin' has added a verse here that further illustrates Poet Hart's thesis: "You know I went to make a swing out with my woman and a 'rat' fell from her head like one from a burning barn."

Lightnin' has never been exposed to the term traditional song, but his first hand understanding is perhaps more eloquent than the scholar's definition: "Some are songs I make. Then, too. some that I sing are songs that everybody has — but course everybody got 'em different. That's songs that somebody else has made. I don't know who it might be, then I hear it, and then I make it my own way. Course it's gonna be the same song, but too it's different." About a third of what Lightnin' sings — represented here by Santa Fe Blues, When The Saints Go Marching In, Bottle Up and Go. and Trouble In Mind — are familiar traditional songs which Lightnin' has in varying degrees personalized to his own satisfaction.

Roughly another third are Lightnin's own compositions which thru repeated singing and reworking have obtained a relatively permanent place in his repertoire. These strike a singular mood and consistent theme however much one performance may differ from another. (On a repeat performance, as recording sometimes necessitates, about half of the verses will be substantially different.) Thus. That Gambling Life, 75 Highway, So Long Baby and Short Haired Woman may be thought of as "standard" members of Lightnin's lore. The last two named have also been absorbed by oral tradition and may now be heard from many blues singers beside their originator.

The remaining third are those fascinating songs which are improvised, heard, and forgotten in the time it takes to sing them. Perhaps these are the most vital representing, as they do, the incredible moment-to-moment process of folk song. Partly stitched together from other sources, but mostly Lightnin's own invention, such songs are created on the spot. Get Off My Toe, The Foot Race Is On, Mama and Papa Hopkins, and In The Evening, the Sun Is Going Down show Lightnin' making a song — songs that follow the turns and twists of thought as readily as a free-association monologue, leaping from subject to subject, bristling with parenthetical comment, flowing over the whole substance of Lightnin's life and having the immediacy of experience itself.

As Lightnin' explains it, "You see, my songs are practically all true songs. They about something real to my way of knowing. Like all that have happened to me is liable to get into my songs. In my family they tell about my grandfather that was a slave that hung himself to escape the bad treatment. Well, that's liable to be in one of my songs. Or that time I was out to Arizona — supposed to be pickin' cotton, but I got to gambling and then I got to going over to Mexico and bringing back wine and bootlegging it to them indians on that government reservation. That's liable to be in a song. Or that time it was trouble up home, or when they got me on the country road gang, or had to say goodbye to some good girl, or be thinking of going to Galveston Beach — all that's liable to come up in my songs. Call 'em true songs."

When Lightnin' speaks of making a song, he's talking of both its composition and its performance as one simultaneous act. Folklorists might well adopt the verb in this sense: to make a song implying the vital process of folk song with its unity between the formation and expression; an ever changing flow where the edges of a single song are never clearly defined. The true folk-singers and their songs are birds in flight. They may be documented thru manuscript and recording, but never captured.

Lightnin' works seven nights a week in Houston and in nearby rural areas and occasionally travels to other parts of the country for brief periods. Every night he's making songs that no one except those present will ever hear.

A remarkable instance of Lightnin's making a song occurred one night in a jook joint when he told a passing waitress to bring him a beer. The girl mumbled something about being busy. Lightnin's retort was a song: "Oh, she's black and she's evil." Lifting a hand to point out the intimidated girl scurrying thru the crowd, he cried, "Oh, that's somebody's black and evil woman." After two verses pursuing this theme, the girl brought him the beer, and Lightnin' sang, "Oh, she's sweet and she's kind … Come walking with a cold beer and says it's mine." Pausing to gulp from the bottle, he smiled at the girl and then slid the bottle (still nearly full) along the guitar strings, letting the whining notes punctuate his singing: "Oh, babe, if you was mine, I'd starch and grind. Oh, babe, if you were mine, I'd carry your water from the boggy bayou." Letting a lingering phrase emphasize the suggestion, he leaned close to the girl, and sang, "Two things I like, that's beer and candy … but you know if you was to give me some candy I'd want it to be sweeter than when it was made."

Because of such gifts, Lightnin's stature among blues singers is unchallenged and is well demonstrated by the recording of other artists. One man has enjoyed success ever since he adopted the name "Lightnin' Slim" and began recording imitations of Lightnin's old records. Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry have recorded a kidding tribute titled A Letter To Lightnin Hopkins. On another level, John S. Wilson has written in the New York Times, "Mr. Hopkins must be counted as one of the best (possibly the best) of the unalloyed country blues men still singing."

Yet the ultimate test of any art is its ability to communicate itself beyond its native culture. And so, partly out of his innate eagerness to go out and astound strange audiences, Lightnin' has begun appearing as a concert artist — the same concert he has given on Southern sidewalks all his life, but before audiences unschooled, perhaps even unsympathetic, to the blues idiom.

On a Hootenanny-in-the-Round at Houston's Alley Theater it was an audience that giggled at the bizarre name Blind Lemon Jefferson when Lightnin' told of his childhood association with the great Texas blues minstrel. Had Lightnin' been a lesser artist or one capable of the usual show business attitudes, he would have limited himself to the familiar and orthodox blues such as Trouble In Mind. Instead the audience saw a wiry, dark man with brilliantly polished shoes amble out to center stage and begin casually talking about a tornado he'd once seen sweeping across the Texas blacklands. He told them, "It cause me to make a song … " and then folding himself over the guitar he let a suspended introduction feed the rising sense of expectation. Before he'd completed more than the second verse of That Mean Old Twister (included in Tradition TLP 1035, LIGHTNIN' HOPKINS — COUNTRY BLUES) Lightnin's mastery of the night was evident. It was an audience that had heard about such folk singers in books and had heard folk songs from professional entertainers. Their encounter with Lightnin' was a revelation. Artist and audience, who moments before had been ignorant of each other, had found common ground thru the impact of Lightnin's personality, the self-evident spontaneity of every moment, and the deeply personal expression of a vital people's music.

Lightnin' startled them with the raw stuff of traditional music and they roared approval. He sang about his own sex habits, hoboing, and the big white boss at cotton picking time. His sudden gestures and dramatically held poses made each song an event. A gold toothed smile mocked his own comments. Midway in a song telling about his days on the chain gang, he lifted a trouser leg to show the angry scar where the leg iron had been. He flung himself into the characteristic little dance he uses to dispel the emotional grip of each song, then brushed a hand across his own kinky hair and sang "I don't want no woman whose hair ain't no longer'n mine … "

— Mack McCormick