|

|

Sleeve Notes

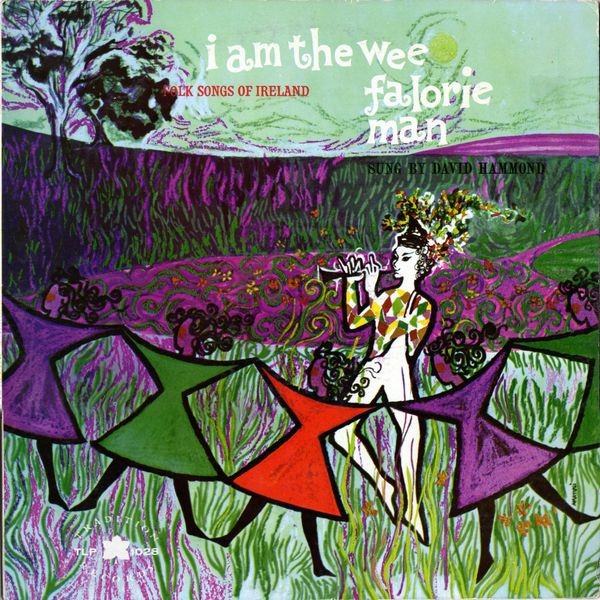

Belfast, where David Hammond was born, is an industrial city flanked by green hills and looking out eastwards on a quiet sea-lough. For the last three centuries it has drawn its life-blood from the surrounding countryside and very few of its half-million inhabitants are more than two generations removed from the soil. In such surroundings David in early boyhood picked up a vast store of traditional songs — from the children playing with dim on the streets, from factory workers chanting and singing on the way home from their daily tasks and from old men and women who remembered in their city pent-houses the songs of the green fields of their youth.

Belfast, where David Hammond was born, is an industrial city flanked by green hills and looking out eastwards on a quiet sea-lough. For the last three centuries it has drawn its life-blood from the surrounding countryside and very few of its half-million inhabitants are more than two generations removed from the soil. In such surroundings David in early boyhood picked up a vast store of traditional songs — from the children playing with dim on the streets, from factory workers chanting and singing on the way home from their daily tasks and from old men and women who remembered in their city pent-houses the songs of the green fields of their youth.

Not all these songs were of Irish origin, for in Ulster's history, English and Scots colonists brought to the province their own particular cultures, and their songs in time have become part of the Irishman's tradition. He has modified them, of course, and dressed them frequently in the garb of Irish melody, so that only a skilled musicologist would dare to say they are not native to the soil. Belfast's traditional songs are a most fascinating admixture of Irish, English and Scots elements.

In his early youth David, who spends a large part of his leisure time walking in the countryside, came to know and love the songs of rural Ulster. On his journeys through six of Ireland's fairest counties, round by the shores of Lough Neagh and over the mountain passes of the Sperrins and the Mournes, he has collected for your entertainment and interest songs from shepherds, weavers, cobblers, fishermen and tinkers — songs of occupation and idleness, songs of love, sorrow and jollification, and even a few of those unblushingly senseless trifles that have amused simple folk all over the world since men first began to sing.

These native airs are not debased by alien graces and they are sung simply, with a minimum of accompaniment, in a traditional style which is not a carbon copy of anybody else's. He has been described by a shrewd critic as a "creative traditionalist," an entirely appropriate phrase. The personality of the singer shines through.

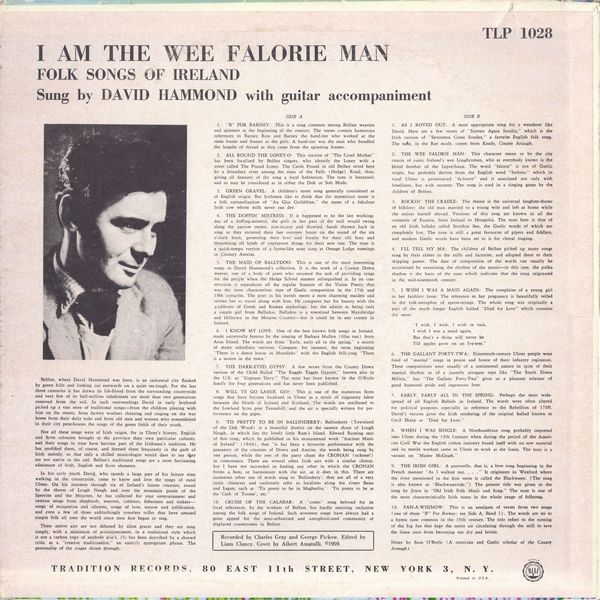

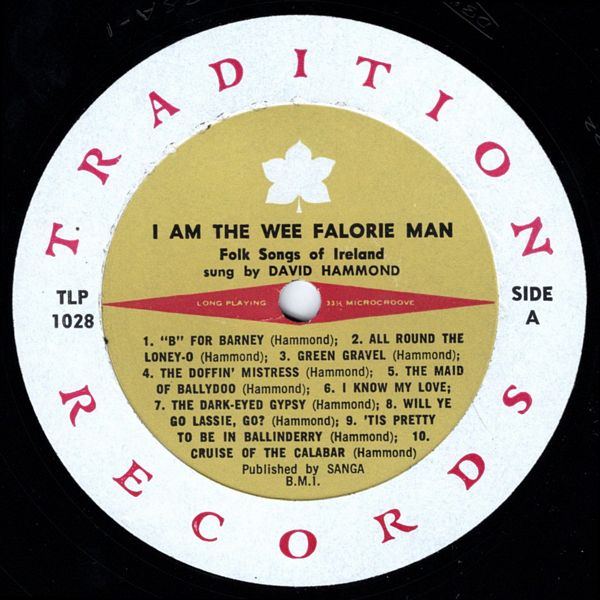

"B" FOR BARNEY: This is a song common among Belfast weavers and spinners at the beginning of the century. The verses contain humorous references to Barney Ross and Barney the band-tier who worked at the same looms and frames as the girls. A band-tier was the man who bundled the lengths of thread as they came from the spinning frames.

ALL ROUND THE LONEY-O: This version of "The Cruel Mother" has been localized by Belfast singers, who identify the Loney with a street called The Pound Loney. The Cattle Pound in old Belfast stood here by a boundary river among the trees of the Falls (Hedge) Road; thus, giving all features of the song a local habitation. The tune is hexatonic and so may be considered as in either the Doh or Soh Mode.

GREEN GRAVEL: A children's street song generally considered as of English origin. But Irishmen like to think that the mysterious name is a folk rationalization of "An Glas Gaibhlinn," the name of a fabulous Irish cow whose milk never ran dry.

THE DOFFIN' MISTRESS: If it happened to be the last working- day of a doffing-mistress, the girls in her part of the mill would swing along the narrow streets, arm-in-arm and shawled, heads thrown back in song as they escorted their late overseer home on the sound of the six o'clock horn, protesting their love and loyalty for their old boss and threatening all kinds of unpleasant things for their new one. The tune is a quick-tempo version of a hymn-like tune sung at Orange Lodge meetings in Country Antrim.

THE MAID OF BALLYDOO: This is one of the most interesting songs in David Hammond's collection. It is the work of a County Down weaver, one of a body of poets who assumed the task of providing songs for the people when the Hedge School masters relinquished it. In its con struction it reproduces all the regular features of the Vision Poetry that was the most characteristic type of Gaelic composition in the 17th and 18th centuries. The poet in his travels meets a most charming maiden and invites her to travel along with him. He compares her for beauty with the goddesses of Greek and Roman mythology, but she admits to being only a simple girl from Ballydoo. Ballydoo is a townland between Mayobridge and Hilltown in the Mourne Country — but it could be in any county in Ireland.

I KNOW MY LOVE: One of the best known folk songs in Ireland, made universally famous by the singing of Barbara Mullen (film star) from Aran Island. The words are from "Early, early all in the spring," a source of many subsidiary versions. Compare, for instance, the verse beginning "There is a dance house in Maradyke" with the English folk-song "There is a tavern in the town."

THE DARK-EYED GYPSY: A few verses from the County Down version of the Child Ballad "The Raggle Taggle Gypsies," known also in the U.S. as "Gypsum Davy." The tune has been known in the O'Boyie family for four generations and has never been published.

WILL YE GO LASSIE, GO?: This is one of the numerous Scots songs that have become localized in Ulster as a result of migratory labor between the North of Ireland and Scotland. The words are attributed to the Lowland Scots poet Tannahill, and the air is specially written for performance on the pipes.

'TIS PRETTY TO BE IN BALLINDERRY: Ballinderry (Townland of the Oak Wood) is a beautiful district on the eastern shore of Lough Neagh, in which lies the lovely little Ram's Island. Edward Bunting says of this song, which he published in his monumental work "Ancient Music of Ireland" (1840), that "it has been a favourite performance with the peasantry of the counties of Down and Antrim, the words being sung by one person, while the rest of the party chant the CRONAN (ochone!) in consonance. There are several other Irish airs with a similar chorus, but I have not succeeded in finding any other in which the CRONAN forms a bass, or harmonizes with the air, as it does in this. There are numerous other sets of words sung to 'Ballinderry'; they are all of a very rustic character and uniformly refer to localities along the rivers Bann and Lagan, such as 'Tis pretty to be in Magherlin,' 'Tis pretty to be at the Cash of Toome', etc."

CRUISE OF THE CALABAR: A "comic" song beloved for its local references, by the workers of Belfast, but hardly meriting inclusion among the folk songs of Ireland. Such nonsense songs have always had a great appeal for the semi-urbanized and unsophisticated community of displaced countrymen in Belfast.

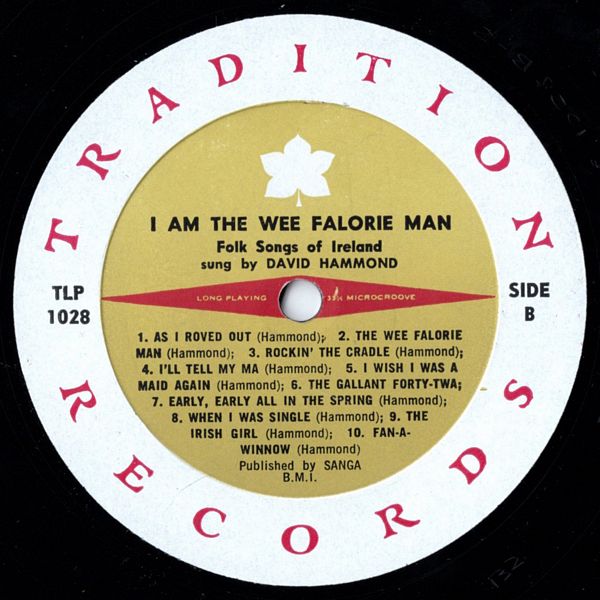

AS I ROVED OUT: A most appropriate song for a wanderer like David. Here are a few verses of "Sixteen Again Sunday," which is the Irish version of "Seventeen Come Sunday," a favorite English folk song. The tune, in the Ray mode, comes from Keady, County Armagh.

THE WEE FALORIE MAN: This character seems to be the city cousin of rustic Ireland's wee Loughryman, who as everybody knows is the blood brother of the Leprechaun. The word "falorie" is not of Gaelic origin, but probably derives from the English word "forlorn" which in rural Ulster is pronounced "fa-loorn" and is associated not only with loneliness, but with mystery. The song is used in a singing game by the children of Belfast.

ROCKIN' THE CRADLE: The theme is the universal laughter-theme of folklore: the old man married to a young wife and left at home while she enjoys herself abroad. Versions of this song are known in all the countries of Eurasia, from Ireland to Mongolia. The tune here is that of an old Irish lullaby called Seoithin Seo, the Gaelic words of which are completely lost. The tune is still a great favourite of pipers and fiddlers, and modern Gaelic words have been set to it for choral singing.

I'LL TELL MY MA: The children of Belfast picked up many songs sung by their elders in the mills and factories, and adopted them to their skipping games. The date of composition of the words can usually be ascertained by examining the rhythm of the music — in this case, the polka rhythm is the basis of the tune which indicates that the song originated in the mid-nineteenth century.

I WISH I WAS A MAID AGAIN: The complaint of a young girl to her faithless lover. The reference to her pregnancy is beautifully veiled in the folk-metaphor of apron-strings. The whole song was originally a part of the much longer English ballad "Died for Love" which contains the verse:

"I wish, I wish, I wish in vain,

I wish I was a maid again.

But that's a thing will never be

Till apples grow on an Ivy-tree."

THE GALLANT FORTY-TWA: Nineteenth-century Ulster people were fond of "martial" songs in praise and honor of their infantry regiments. These compositions were usually of a sentimental nature in spite of their martial rhythm or of a jauntily arrogant type like "The South Down Militia," but "The Gallant Forty-Twa" gives us a pleasant mixture of good humored pride and ingenuous love.

EARLY, EARLY ALL IN THE SPRING: Perhaps the most wide spread of all English Ballads in Ireland. The words were often altered for political purposes especially in reference to the Rebellion of 1789. David's version gives the Irish rendering of the original ballad known to Cecil Sharp as "Died for Love."

WHEN I WAS SINGLE: A Northumbrian song probably imported into Ulster during the 19th Century when during the period of the American Civil War the English cotton industry found itself with no raw material and its textile workers came to Ulster to work at the linen. The mac is a variant on "Master McGrath."

THE IRISH GIRL: A pastorelle, that is, a Jove song beginning in the French manner "As I walked out … "It originates in Wexford where the river mentioned in the first verse is called the Blackwater. (The song is also known as "Blackwaterside.") The present tide was given to the song by Joyce in "Old Irish Folk Music and Song." The tune is one of the most characteristically Irish tunes in the whole range of folksong.

FAN-A-WINNOW: This is an amalgam of verses from two songs (one of them "B" For Barney: see Side A, Band 1). The words are set to a hymn tune common in the 19th century. The title refers to the turning of the big fan that kept the moist air circulating through the mill to save the linen yarn from becoming too dry and brittle.

Notes by Seán O'Boyle (A musician and Gaelic scholar of the County Armagh)