|

|

Sleeve Notes

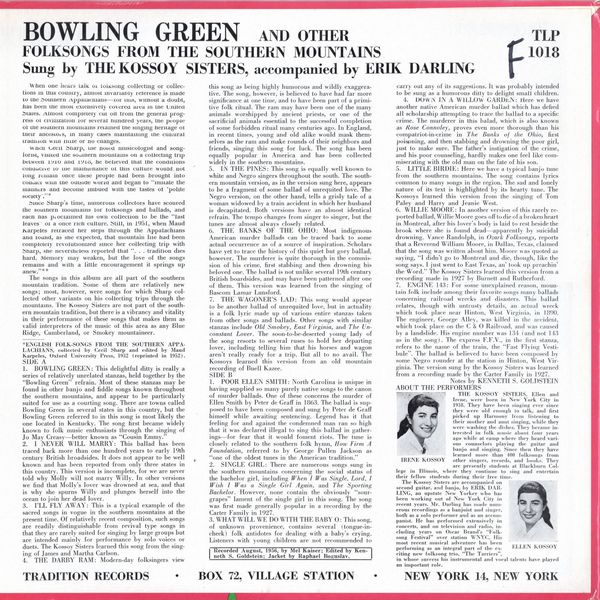

When one hears talk of folksong collecting or collections in this country, almost invariably reference is made to the Southern Appalachians — for this, without a doubt, has been the most extensively covered area in the United states. Almost completely cut off from the general progress or civilization by several hundred years, the people of the southern mountains retained the singing heritage of their ancestors, in many cases maintaining the cultural tradition with little or no changes.

When Cecil Sharp, the noted musicologist and songlorist, visited me southern mountains on a collecting trip between 1916 and 1918, he believed that the conditions conducive to the maintenance of this culture would not long remain once these people had been brought into contact with the outside world and began to "imitate the manners and become imbued with the tastes of polite society."*

Since Sharp's time, numerous collectors have scoured the southern mountains for folksongs and ballads, and each has proclaimed his own collection to be the "last leaves" of a once rich culture. Still, in 1951, when Maud Karpeles retraced her steps through the Appalachians and found, as she expected, that mountain life had been completely revolutionized since her collecting trip with Sharp, she nevertheless reported that "tradition dies hard. Memory may weaken, but the love of the songs remains and with a little encouragement it springs up anew."*

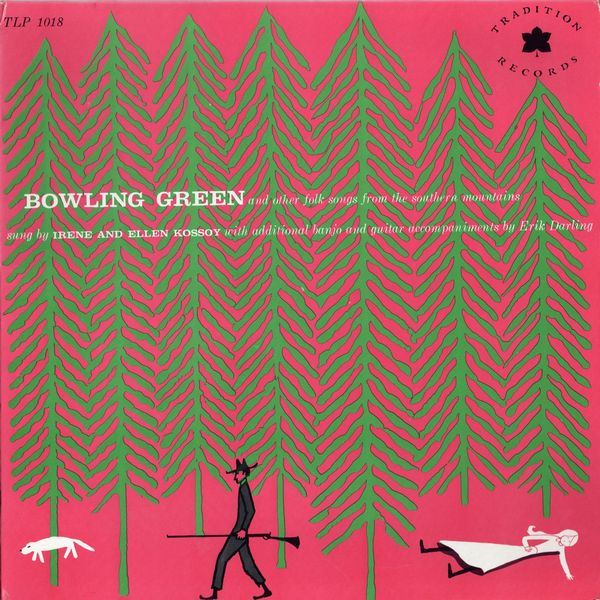

The songs in this album are all part of the southern mountain tradition. Some of them are relatively new songs; most, however, were songs for which Sharp collected other variants on his collecting trips through the mountains. The Kossoy Sisters are not part of the southern mountain tradition, but there is a vibrancy and vitality in their performance of these songs that makes them as valid interpreters of the music of this area as any Blue Ridge, Cumberland, or Smokey mountaineer.

ENGLISIH FOLK-SONGS FROM THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS, collected by Cecil Sharp and edited by Maud Karpeles, Oxford University Press, 1932 (reprinted in 1952).

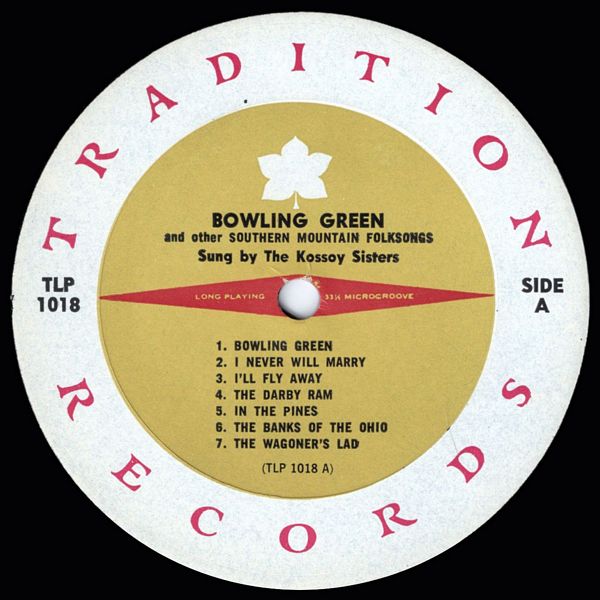

BOWLING GREEN: This delightful ditty is really a series of relatively unrelated stanzas, held together by the "Bowling Green" refrain. Most of these stanzas may be found in other banjo and fiddle songs known throughout the southern mountains, and appear to be particularly suited for use as a courting song. There are towns called Bowling Green in several states in this country, but the Bowling Green referred to in this song is most likely the one located in Kentucky. The song first became widely known to folk music enthusiasts through the singing of Jo May Creasy — better known as "Cousin Emmy."

I NEVER WILL MARRY: This ballad has been traced back more than one hundred years to early 19th century British broadsides. It does not appear to be well known and has been reported from only three states in this country. This version is incomplete, for we are never told why Molly will not marry Willy. In other versions we find that Molly's lover was drowned at sea, and that is why she spurns Willy and plunges herself into the ocean to join her dead lover.

I'LL FLY AWAY: This is a typical example of the sacred songs in vogue in the southern mountains at the present time. Of relatively recent composition, such songs are readily distinguishable from revival type songs in that they are rarely suited for singing by large groups but are intended mainly for performance by solo voices or duets. The Kossoy Sisters learned this song from the singing of James and Martha Carlson.

THE DARBY RAM: Modern-day folksingers view this song as being highly humorous and wildly exaggerative. The song, however, is believed to have had far more significance at one time, and to have been part of a primitive folk ritual. The ram may have been one of the many animals worshipped by ancient priests, or one of the sacrificial animals essential to the successful completion of some forbidden ritual many centuries ago. In England, in recent times, young and old alike would mask themselves as the ram and make rounds of their neighbors and friends, singing this song for luck. The song has been equally popular in America and has hen collected widely in the southern mountains,

IN THE PINES: This song is equally well known to white and Negro singers throughout the south. The southern mountain version, as in the version sung here, appears to be a fragment of some ballad of unrequited love. The Negro version, on the other hand, tells a grisly tale of a woman widowed by a train accident in which her husband is decapitated. Both versions have an almost identical refrain. The tempo changes from singer to singer, but the tunes are almost always closely related.

THE BANKS OF THE OHIO: Most indigenous American murder ballads can be traced back to some actual occurrence as of a source of inspiration. Scholars have yet to trace the history of this quiet but gory ballad, however. The murderer is quite thorough in the commission of his crime, first stabbing and then drowning his beloved one. The ballad is not unlike several 19th century British boardsides, arid may have been patterned after one of them. This version was learned from the singing of Bascom Lamar Lunsford,

THE WAGONER'S LAD: This song would appear to be another ballad of unrequited love, but in actuality is a folk lyric made up of various entire stanzas taken from other songs and ballads. Other songs with similar stanzas include Old Smokey, East Virginia, and The Un-constant Lover. The soon-to-be-deserted young lady of the song resorts to several ruses to hold her departing lover, including telling him that his horses and wagon aren't really ready for a trip. But all to no avail. The Kossoys learned this version from an Old mountain recording of Buell Kazee.

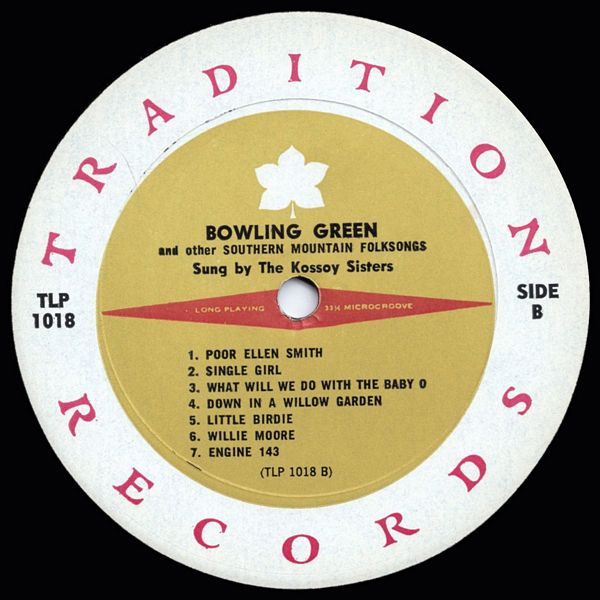

POOR ELLEN SMITH: North Carolina is unique in having supplied so many purely native songs to the canon of murder ballads. One of these concerns the murder of Ellen Smith by Peter de Graff in 1863. The ballad is supposed to have been composed and sung by Peter de Graff himself while awaiting sentencing. Legend has it that feeling for arid against the condemned man ran so high that it was declared illegal to sing this ballad in gatherings — for fear that it would foment riots. The tune is closely related to the southern folk hymn, How Firm A Foundation, referred to by George Pullen Jackson as "one of the oldest tunes in the American tradition."

SINGLE GIRL: There are numerous songs sung in the southern mountains concerning the social status of the bachelor girl, including When I Was Single, Lord, I Wick I Was a Single Girl Again, and The Sporting Bachelor. However, none contain the obviously "sour-grapes" lament of the single girl in this song. The song was first made generally popular in a recording by the Carter Family in 1927.

WHAT WILL WE DO WITH THE BABY O: This song, of unknown provenience, contains several (tongue-in-cheek) folk antidotes for dealing with a baby's crying. Listeners with young children are not recommended to carry out any of its suggestions. It was probably intended to be sung as a humorous ditty to delight small children.

DOWN IN A WILLOW GARDEN: Here we have another Native American murder ballad which has defied all scholarship attempting to trace the ballad to a specific crime. The murderer in this ballad, which is also known as Rose Connoley, proves even more thorough than his compatriot-in-crime in The Banks of the Ohio, first poisoning, and then stabbing and drowning the poor girl, just to make sure. The father's instigation of the crime, and his poor counseling, hardly makes one feel like commiserating with the old man on the fate of his son.

LITTLE BIRDIE: Here we have a typical banjo tune from the southern mountains. The song contains lyrics common to many songs in the region. The sad and lonely nature of its text is highlighted by its hearty tune. The Kossoys learned this version from the singing of Tom Paley and Harry and Jeanie West.

WILLIE MOORE: In another version of this rarely reported ballad, Willie Moore goes off to die of a broken heart in Montreal, after his lover's body is laid to rest beside the brook where she is found dead — apparently by suicidal drowning. Vance Randolph, in Ozark Folksongs, reports that a Reverend William Moore, in Dallas, Texas, claimed that the song was written about him. Moore was quoted as saying, "I didn't go to Montreal and die, though, like the song says. I just went to East Texas, an' took up preachin' the Word." The Kossoy Sisters learned this version from a recording made in 1927 by Burnett and Rutherford.

ENGINE 143: For some unexplained reason, mountain folk include among their favorite songs many ballads concerning railroad wrecks and disasters. This ballad relates, though with untrusty details, an actual wreck which took place near Hinton, West Virginia, in 1890. The engineer, George Alley, was killed in the accident, which took place on the C & O Railroad, and was caused by a landslide. His engine number was 134 (and not 143 as in the song). The express F.F.V., in the first stanza, refers to the name of the train, the "Fast Flying Vestibule". The ballad is believed to have been composed by some Negro rounder at the station in Hinton, West Virginia, The version sung by the Kossoy Sisters was learned from a recording made by the Carter Family in 1927.

Notes by KENNETH S. GOLDSTEIN

ABOUT THE PERFORMERS

THE KOSSOY SISTERS, Ellen and Irene, were born in New York City in 1938. They have been singing ever since they were old enough to talk, and first picked up Harmony from listening to their mother and aunt singing, while they were washing the dishes. They became interested in folk music about four years ago while at camp where they heard various counselors playing the guitar and banjo and singing. Since then they have learned more than 400 folksongs from other singers, records, and books. They are presently students at Blackburn College in Illinois, where they continue to sing and entertain their fellow students during their free time.

The Kossoy Sisters are accompanied on second guitar, and banjo, by ERIK DARLING, an upstate New Yorker who has been working out of New York City in recent years. Mr. Darling has made numerous recordings as a banjoist and singer, both as a solo performer and as an accompanist. He has performed extensively in concerts, and on television and radio, including years on Oscar Brand's "Folksong Festival" over station WNYC. His most recent musical adventure has been performing as an integral part of the exciting new folksong trio. "The Tarriers", in whose success his instrumental and vocal talents have played an important role.