|

|

|

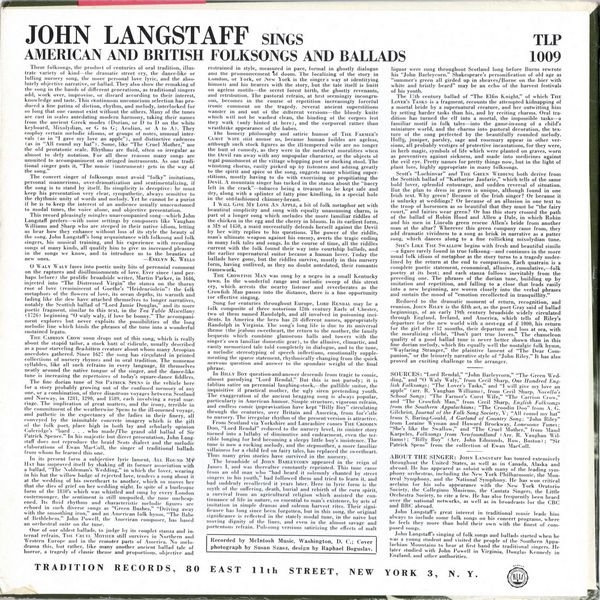

Sleeve Notes

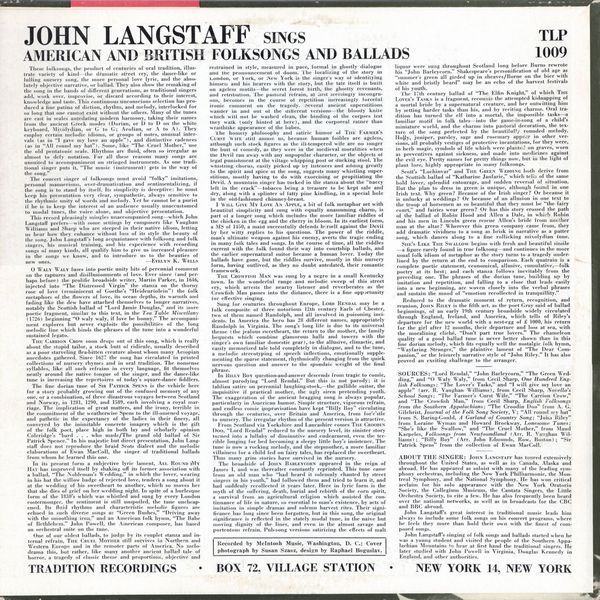

These folksongs, the product of centuries of oral tradition, illustrate variety of kind — the dramatic street cry, the dance — like or lulling nursery song, the more personal love lyric, and the absolutely objective narrative, or ballad. They also show the remaking of the song in the hands of different generations, as traditional singers add, work over, improvise, or discard according to their interest, knowledge and taste. This continuous unconscious selection has produced a fine patina of diction, rhythm, and melody, interlocked for so long that one cannot exist without the others. Many of the tunes are cast in scales antedating modern harmony, taking their names from the ancient Greek modes (Dorian, or D to P on the white keyboard, Mixolydian, or G to G; Aeolian, or A to A). They employ certain melodic idioms, or groups of notes, unusual intervals (as in "I gave my love an apple"), and distinctive cadences (as in "All round my hat"). Some, like "The Cruel Mother," use the old pentatonic scale. Rhythms are fluid, often so irregular as almost to defy notation. For all these reasons many songs are unsuited to accompaniment on stringed instruments. As one traditional singer puts it, "The music (instrument) gets in the way of the song."

The concert singer of folksongs must avoid "folky" imitations, personal mannerisms, over-dramatization and sentimentalizing, if the song is to stand by itself. Its simplicity is deceptive: he must keep his presentation very clear, sympathetic, always sensitive to the rhythmic unity of words and melody. Yet he cannot be a purist if he is to keep the interest of an audience usually unaccustomed to modal tunes, the voice alone, and objective presentation.

This record pleasingly mingles unaccompanied song — which John Langstaff prefers — with sonic settings by composers like Vaughan Williams and Sharp who are steeped in their native idiom, letting us hear how they enhance without loss of its style the beauty of tile song. John Langstaff's long acquaintance with folksong and folk singers, his musical training, and his experience with recording songs of many kinds, all qualify him to give us increased pleasure in the songs we know, and to introduce us to the beauties of new ones.

— EVELYN K. WELLS

O WALY WALY fuses into poetic unity bits of perennial comment on the raptures and disillusionments of love. Ever since (and perhaps before) the prolific broadside writer, Martin Parker, in 1646, injected into "The Distressed Virgin" the stanza on the thorny rose of love (reminiscent of Goethe's "Heidenrölein") the folk metaphors of the flowers of love, its ocean depths, its warmth and fading like the dew have attached themselves to longer narratives, notably the Scottish ballad of "Lord Jamie Douglas," and its more poetic fragment, similar to this text, in the Tea Table Miscellany (1726) beginning "O waly waly, if love be bonny." The accompaniment explores but never exploits the possibilities of the long melodic line which binds the phrases of the tune into a wonderful sustained legato.

THE CARRION CROW soon drops out of this song, which is really about the stupid tailor, a stock butt of ridicule, usually described as a poor starveling flea-bitten creature about whom many Aesopian anecdotes gathered. Since 1627 the song has circulated in printed collections of nursery rhymes and in oral tradition. The nonsense syllables, like all such refrains in every language, fit themselves neatly around the native tongue of the singer, and the dance-like tune is increasing the repertoires of today's square-dance fiddlers.

The fine dorian tune of SIR PATRICK SPENS is the vehicle here for a story probably growing out of the confused memory of any one, or a combination, of three disastrous voyages between Scotland and Norway, in 1281, 1290, and 1589, each involving a royal marriage. The implication of great matters, and the irony, terrible in the commitment of the weatherwise Spens to the ill-omened voyage, and pathetic in the expectancy of the ladies in their finery, all conveyed by the inimitable concrete imagery which is the gift of the folk poet, place high in both lay and scholarly opinion Coleridge's "bard — . . who made/The grand old ballad of Sir Patrick Spence." In his majestic but direct presentation, John Langstaff does not reproduce the braid Scots dialect and the melodic elaborations of Ewan MacColl, the singer of traditional ballads from whom he learned this one.

In its present form a subjective lyric lament, ALL ROUND MY HAT has improved itself by shaking off its former association with a ballad, "The Nobleman's Wedding," in which the lover, wearing in his hat the willow badge of rejected love, tenders a song about it at the wedding of his sweetheart to another, which so moves her that she dies of grief on her wedding night. In spite of a burlesque form of the 1830's which was whistled and sung by every London costermonger, the sentiment is still unspoiled, the tune uncheapened. Its fluid rhythms and characteristic melodic figures are echoed in such diverse songs as "Green Bushes," "Driving away with the smoothing iron," and an American folk hymn, "The Babe of Bethlehem." John Powell, the American composer, has based an orchestral suite on the tune.

One of our oldest ballads, to judge by its couplet stanza and internal refrain, THE CRUEL MOTHER still survives in Northern and Western Europe and in the remoter parts of America. No melodrama this, but rather, like many another ancient ballad tale of horror, a tragedy of classic theme and proportions, objective and restrained in style, measured in pace, formal in ghostly dialogue and the pronouncement of doom. The localizing of the story in London, or York, or New York is the singers way of identifying himself and his hearers with the story, but the tale itself is built on ageless motifs — the secret forest birth, the ghostly revenants, and retribution. The pastoral refrain, at first seemingly incongruous, becomes in the course of repetition increasingly forceful ironic comment on the tragedy. Several ancient superstitions wander in and out of the different versions — the bloody knife which will not be washed clean, the binding of the corpses lest they walk (only hinted at here), and the corporeal rather than wraithlike appearance of the babes.

The homely philosophy and satiric humor of THE FARMER'S CURST WIFE still amuse us, because human foibles are ageless, although such stock figures as the ill-tempered wife are no longer the butt of comedy, as they were in the medieval moralities when the Devil ran away with any unpopular character, or the objects of legal punishment at the village whipping post or ducking stool. The whistling chorus, easily picked up by listeners and adding greatly to the spirit and spice of the song, suggests many whistling superstitions, mostly having to do with exorcising or propitiating the Devil. A mountain singer has tucked in the stanza about the "baccy left in the crack" — tobacco being a treasure to be kept safe and dry, along with a splinter of fatty pine kindling, in a special hole in the old-fashioned chimney-breast.

I WILL GIVE MY LOVE AN APPLE, a bit of folk metaphor set with beautiful simplicity and sung with equally unassuming charm, is part of a longer song which includes the more familiar riddles of the chicken in the egg and the cherry in bloom. In its earliest form, a MS of 1450, a maid successfully defends herself against the Devil by her witty replies to his questions. The power of the riddle, man's ultimate weapon against his enemy, averts the tragic ending in many folk tales and songs. in the course of time, all the riddles current with the folk found their way into courtship ballads, and the earlier supernatural suitor became a human lover. Today the ballads have gone, but the riddles survive, mostly in this nursery form, having outlived, as they no doubt antedated, their romantic framework.

THE CROWFISH MAN was sung by a negro in a small Kentucky town. In the wonderful range and melodic sweep of this Street cry, which arrests the nearby listener and reverberates as the Crowfish Man passes into the distance, there is a fine opportunity for effective singing.

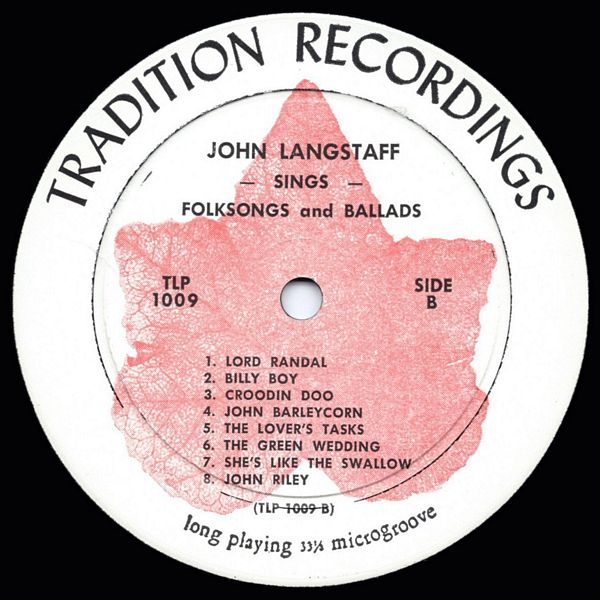

Sung for centuries throughout Europe, LORD RENDAL may be a folk composite of three notorious 12th century Earls of Chester, two of them named Randolph, and all involved in poisoning incidents. In America the hero has 28 different names, appropriately Randolph in Virginia. The song's long life is due to its universal theme (the jealous sweetheart, the return to the mother, the family bequests which combine glamorous halls and towers with the singer's own familiar domestic gear), to the allusive, climactic, and easily memorized tale told completely in dialogue, and to the tune, a melodic stereotyping of speech inflections, emotionally supplementing the sparse statement, rhythmically changing from the quick nervous question and answer to the spondaic weight of the final phrase.

In BILLY BOY question-and-answer descends from tragic to comic, almost parodying "Lord Rendal." But this is not parody; it is fabliau satire on perennial laughing-stock, — the gullible suitor, the inquisitive if practical mother, the ugly siren pretending youth. The exaggeration of the ancient bragging song is always popular, particularly in American humor. Simple structure, vigorous refrain, and endless comic improvisation have kept "Billy Boy" circulating through the centuries, over Britain and America, from for'c'stle to nursery. The irregular rhythm of the present version is attractive.

From Scotland via Yorkshire and Lancashire comes THE CROODIN DOO, "Lord Rendal" reduced to the nursery level, its sinister story turned into a lullaby of diminutive and endearment, even the terrible longing for bed becoming a sleepy little boy's insistence. The tune is now a rocking melody, and the stepmother, a more familiar villainess for a child fed on fairy tales, has replaced the sweetheart. Thus many grim stories have survived in the nursery.

The broadside of J0HN BARLEYCORN appeared in the reign of James I, and was thereafter constantly reprinted. This tune came from an old man who "had heard it solemnly chanted by Street singers in his youth," had followed them and tried to learn it, and had suddenly recollected it years later. Here in lyric form is the myth of the suffering, death, burial and rebirth of the corn spirit, a survival from an agricultural religion which assisted the continuance of life in nature, so essential to man's existence, by acts of imitation in simple dramas and solemn harvest rites. Their significance has long since been forgotten, but in this song, the original significance is reflected in the stately modal tune, in the naive but moving dignity of the lines, and even in the almost savage and portentous refrain. Pub-song versions satirizing the effects of malt liquor were sung throughout Scotland long before Burns rewrote his "John Barleycorn." Shakespeare's personification of old age us "summer's green all girded up in sheaves/Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard" may be an echo of the harvest festivals of his youth.

The 17th century ballad of "The Elfin Knight," of which THE LOVER'S TASKS is a fragment, recounts the attempted kidnapping of a mortal bride by a supernatural creature, and her outwitting him by setting harder tasks than his, and by reciting charms. Oral tradition has turned the elf into a mortal, the impossible tasks — a familiar motif in folk tales — into the game-in-song of a child's miniature world, and the charms into pastoral decoration, the texture of the song perfected by the beautifully rounded melody. Holly, juniper, parsley, sage and rosemary appear in other versions, all probably vestiges of protective incantations, for they were, in herb magic, symbols of life which were planted on graves, worn as preventives against sickness, and made into medicines against the evil eye. Pretty names for pretty things now, but in the light of plant lore, highly appropriate in many folksongs.

Scott's "Lochinvar" and THE GREEN WEDDING both derive from the Scottish ballad of "Katharine Janfarie," which tells of the same bold lover, splendid entourage, and sudden reversal of situation. But the plan to dress in green is unique, although found in one Irish text. Why green? Because of the Irish singer? Or because it is unlucky at weddings? Or because of an allusion in one text to the troop of horsemen as so beautiful that they must be "the fairy court," and fairies wear green? Or has this story crossed the path of the ballad of Robin Hood and Allen a Dale, in which Robin and his men in Lincoln green rescue Allen's bride from another man at the altar? Wherever this green company came from, they add dramatic vividness to a song as brisk in narrative as a putter song, which dances along to a fine rollicking mixolydian tune.

SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW begins with fresh and beautiful simile — a figure rarely found in true folksong — and continues in the more usual folk idiom of metaphor as the story turns to a tragedy underlined by the return at the end to comparison. Each quatrain is a complete poetic statement, economical, allusive, cumulative, — folk poetry at its best; and each stanza follows inevitably from the preceding one. The phrases of the dorian tune, building up by imitation and repetition, and falling to a close that leads easily into a new beginning, are woven closely into the verbal phrases and sustain the mood of "emotion recollected in tranquility."

Reduced to the dramatic moment of return, recognition, and reunion, JOHN RILEY is the fifth act, as the poet Gray said of ballad beginnings, of an early 19th century broadside widely circulated through England, Ireland, and America, which tells of Riley's departure for the new world with a nest-egg of £1000, his return for the girl after 12 months, their departure and loss at sea, with the moralizing cliché, "Don't part true lovers." The chameleon quality of a good ballad tune is never better shown than in this fine dorian melody, which fits equally well the nostalgic folk hymn, "Wayfaring Stranger," the plaintive lament of "The Dear Companion," or the leisurely narrative style of "John Riley." It has also proved an exciting challenge to the arranger.

SOURCES: "Lord Rendal," "John Barleycorn," "The Green Wed. ding," and "O Waly Waly," from Cecil Sharp, One Hundred English Folksongs; "The Lover's Tasks," and "I will give my love an apple" (arr. R. Vaughan Williams), from Cecil Sharp, Norello's School Songs; "The Farmer's Curst Wife," "The Carrion Crow," and "The Crowfish Man," from Cecil Sharp, English Folksongs from the Southern Appalachians; "The Croodin Doo" from A. G. Gilchrist, Journal of the Folk Song Society, V; "All round my hat" from S. Baring-Gould, A Garland of Country Song; "John Riley" from Loraine Wyman and Howard Brockway, Lonesome Tunes; "She's like the Swallow," and "The Cruel Mother," from Maud Karpeles, Folksongs from Newfoundland (Arr. R. Vaughan Willianis); "Billy Boy" (Arr. John Edniunds, Row, Boston) ; "Sir Patrick Spens" from the collection of Ewan MacColl.

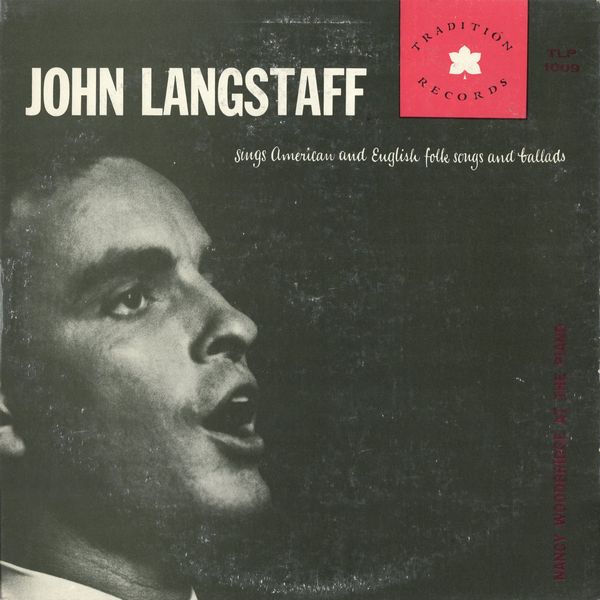

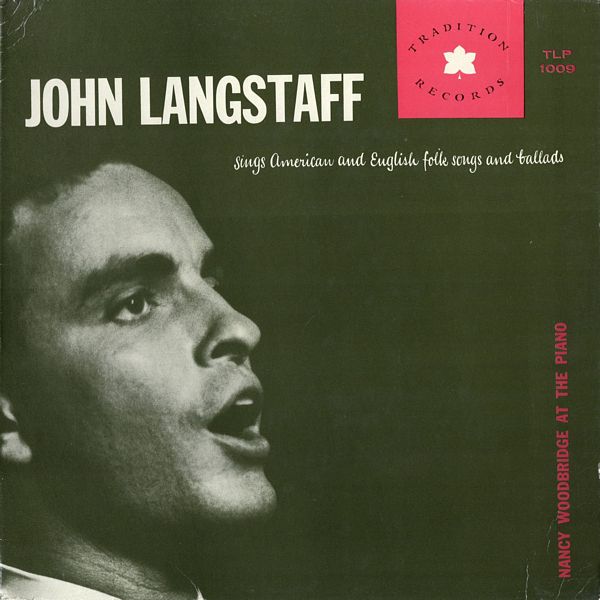

ABOUT THE SINGER: JOHN LANGSTAFF has toured extensively throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, Alaska and abroad. He has appeared as soloist with many of the leading symphony orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic, the Montreal Symphony, and the National Symphony. He has won critical acclaim for his solo appearance with the New York Oratorio Society, the Collegium Musicum, the Cantata Singers, the Little Orchestra Society, to cite a few. He has also frequently been heard over the national networks, as well as in broadcasts for the CBC and BBC abroad.

John Langstaff's great interest in traditional music leads him always to include some folk songs on his concert programs, where he feels they more than hold their own with the finest of composed songs.

John Langstaff's singing of folk songs and ballads started when he was a young student and visited the people of the Southern Appalachian Mountains to hear at first hand the traditional singers. He later studied with John Powell in Virginia, Douglas Kennedy in England. and other authorities.