|

|

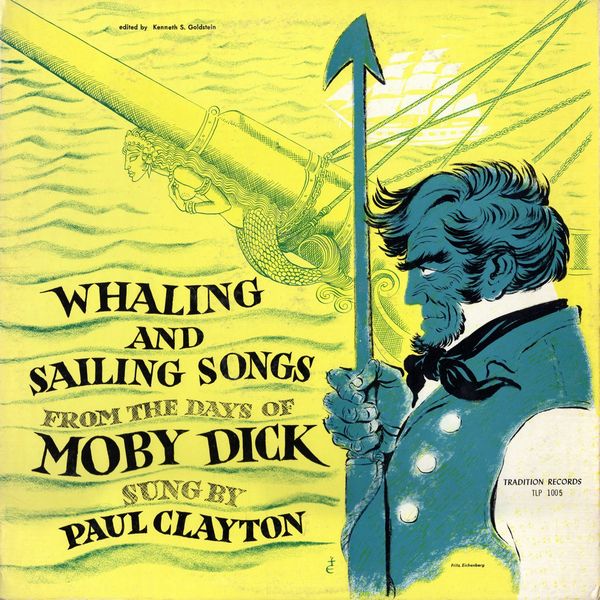

Sleeve Notes

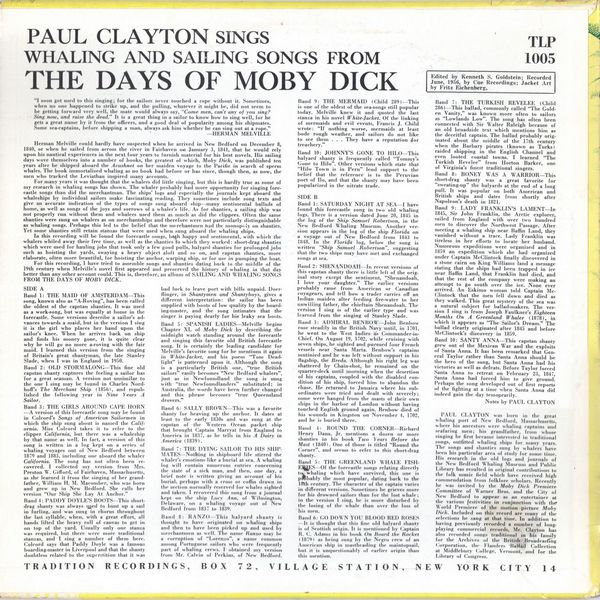

"I soon got used to this singing; for the sailors never touched a rope without it. Sometimes, when no one happened to strike up, and the pulling, whatever it might he, did not seem to be getting forward very well, the mate would always say, "Come men, can't any of you sing? Sing now, and raise the dead." It is a great thing in a sailor to know how to sing well, for he gets a great name by it from the officers, and a good deal of popularity among his shipmates. Some sea-captains, before shipping a man, always ask him whether he can sing out at a rope."

— HERMAN MELVILLE

Herman Melville could hardly have suspected when he arrived in New Bedford on December 8, 1840, or when he sailed front across the river in Fairhaven oil January 3, 1841, that he would rely upon his nautical experiences in the next four years to furnish material for his best novels. His sailing days wove themselves into a number of books, the greatest of which, Moby Dick, was published ten years after he shipped aboard the Acushnet on her maiden voyage to the Pacific in search of sperm whales. The hook immortalized whaling as no book had before or has since, though then, as now, the men who tracked the Leviathan inspired many accounts.

For many years it was thought that she whalers did little singing, but this is hardly true as some of my research in whaling songs has shown. The whaler probably had more opportunity for singing forecastle songs than did the merchantman. The ships' logs and especially tile journals kept aboard the whaleships by individual sailors make fascinating reading. They sometimes include song texts and give an accurate indication of the types of songs sung aboard ship — many sentimental ballads of home, as well as songs of the joys and sorrows of a whaler's life. As for shanties, a sailing ship was not properly run without them and whalers used them as much as did the clippers. Often the same shanties were sung on whalers as on merchantships and therefore were not particularly distinguishable as whaling songs. Perhaps this led to the belief that she merchantmen had the monopoly on shanties. Yet sonic shanties still retain stanzas that were used when sung aboard the whaling ships.

In this recording will be found the forecastle songs, both happy and sentimental, with which the whalers whiled away their free time, as well as the shanties to which they worked: short-drag shanties which were used for hauling jobs that took only a few good pulls, halyard shanties for prolonged jobs such as hoisting the yards, swaying a heavy object aloft and so on, and capstan shanties, more elaborate, often more beautiful, tor hoisting the anchor, warping ship, or for use in pumping the boat.

For this recording, I have tried to assemble songs and shanties dating hark to the middle of the 19th century when Melville's novel first appeared and preserved the history of whaling in that day better than any other account could. This is, therefore, an album, of SAILING AND WHALING SONGS FROM THE DAYS OF MOBY DICK.

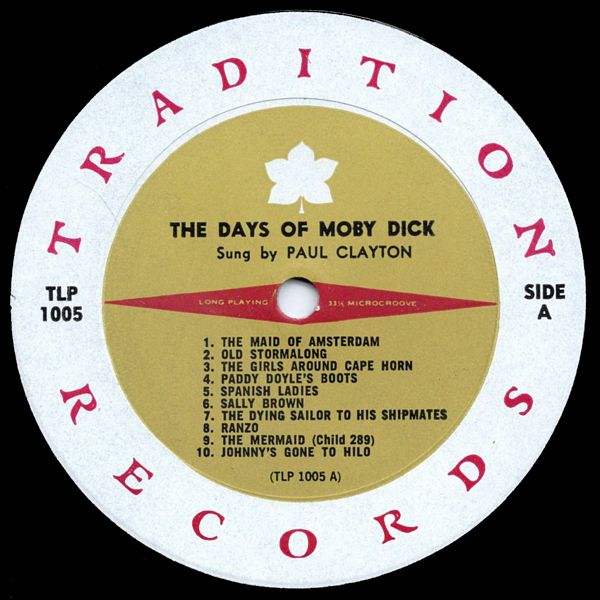

SIDE A

Band 1: THE MAID OF AMSTERDAM — This song, known also as "A-Roving", has been called the oldest of the capstan shanties. It was used as a work-song, but was equally at home in the forecastle. Souse versions describe a sailor's advances towards a maid, but in the version I sing it is the girl who places her hand upon the sailor's knee. When he arrives back on ship and finds his money gone, it is quite clear why he will go no more a-roving with the fair maid. I learned this version from the singing of Britain's great shantyman, the late Stanley Slade, when I was in England in 1950.

Band 2: OLD STORMALONG — This fine old capstan shanty captures the feeling a sailor has for a great seaman. A version not unsimilar to the one I sing may be found in Charles Nordhoff's The Merchant Ship (1856), and republished the following year in Nine Years A Sailor.

Band 3: THE GIRLS AROUND CAPE HORN — A version of this forecastle song may be found in Coleord's Songs of American Sailormen, in which the ship sung about is named the California. Miss Colcord takes it to refer to the clipper California, but there was a whaleship by that name as well. In fact, a version of this song is written in a log kept on a series of whaling voyages out of New Bedford between 1879 and 1883, including one aboard the whaler California. The song has not often been recovered. I collected my version front Mrs. Preston W. Gifford, of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, as she learned it from the singing of her grandfather, William H. M. Macomber, who was born and grew up in New Bedford. She calls her version 'Our Ship She Lay At Anchor."

Band 4: PADDY DOYLE'S BOOTS — This short-drag shanty was always used to bunt up a sail in furling, and was sung in chorus throughout the last syllable, when, with a great effort, all hands lifted the heavy roll of canvas to, get in on top of the yard. Usually only one stanza was required, but there were more traditional stanzas, and I sing a number of them here. Coleord says that Paddy Doyle was a famous boarding-master in Liverpool and that the shanty doubtless related to the superstition that it was bad luck to leave port with bills unpaid. Doerflinger, in Shantymen and Shantyboys, gives a different interpretation: the sailor has been supplied with boots of low quality by the boarding-master, and the song intimates that the singer is paying dearly for his leaky sea boots.

Band 5: SPANISH LADIES — Melville begins Chapter XL of Moby Dick by describing the midnight watch standing around the forecastle and singing this favorite old British forecastle song. It is certainly the leading candidate for Melville's favorite song for he mentions it again in White-Jacket, and his poem "Torn Deadlight" is patterned upon it. Although the song is a particularly British one, "true British sailors" easily becomes "New Bedford whalers", just as in Newfoundland the song is sung with "true Newfoundlanders" substituted; in Australia, the words have been further changed and this phrase becomes "true Queensland drovers."

Band 6: SALLY BROWN — This was a favorite shanty for heaving up the anchor. It dates at least to the early 1830s and was sung at the capstan of the Western Ocean packet ship that brought Captain Marryat from England to America in 1837, as he tells in his A Dairy in America (1839).

Band 7: THE DYING SAILOR TO HIS SHIPMATES — Nothing in shipboard life stirred the whaler's emotions like a burial at sea. A whaling log will contain numerous entries concerning the stale of a sick man, and then, one day, a brief note is written giving an account of his burial, perhaps with a cross or coffin drawn in the section normally reserved for whales sighted and taken. I recovered this song from a journal kept on the ship Lucy Ann, of Wilmington, Delaware, on a whaling voyage out of New Bedford front 1837 to 1839.

Band 8: RANZO — This halyard shanty is thought to have originated on whaling ships and then to have been picked up and used by merchantmen as well. The name Ranzo may be a corruption of "Loreozo", a name common among Portuguese sailors — who were frequently part of whaling crews. I obtained my version from Mr. Calvin of Perkins, of New Bedford.

Band 9: THE MERMAID (Child 289) — This is one of the oldest of the sea-songs still popular today. Melville knew it and quoted the last stanza in his novel White-Jacket. Of the linking of mermaids and evil events, Francis J. Child wrote: "If nothing worse, mermaids at least bode rough weather, and sailors do not like to see them … They have a reputation for treachery."

Band 10: JOHNNY'S GONE TO HILO — This halyard shanty is frequently called "Tommy's Gone to Hilo". Other versions which state that "Hilo Town is in Peru" lend support to the belief that the reference is to the Peruvian port of Ilo, and that the shanty may have been popularized in site nitrate trade.

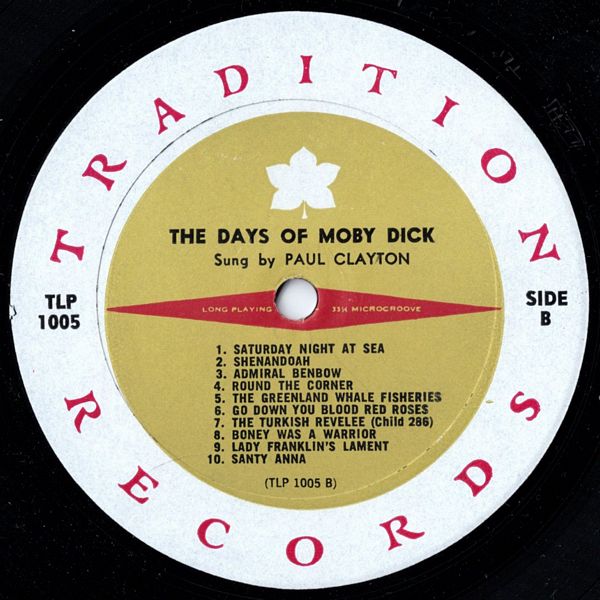

SIDE B

Band 1: SATURDAY NIGHT AT SEA — I have found this forecastle song in two old whaling logs. There is a version dated June 20, 1845 in rise log of the Ship Samuel Robertson, in the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Another version appears in the log of the ship Florida on a voyage out of New Bedford frosts 1843 to 1848. In the Florida log, below the song is written "Ship Samuel Robertson", suggesting that the two ships may have met and exchanged songs at sea.

Band 2: SHENANDOAH — In recent versions of this capstan shanty there is little left of the original story except the sentiment, "Shenandoah, I love your daughter." The earlier versions probably came from American or Canadian voyageurs, and tell how a trader carries off an Indian maiden after feeding fire-water to her unwilling father, the chieftain Shenandoah. The version I sing is of the earlier type and was learned front the singing of Stanley Slade. Spell checked to here…

Band 3: ADMIRAL BENBOW — John Benbow rose steadily in the British Navy until, in 1701, he went' to the West Indies as Commander-in-Chief. On August 19, 1702, while cruising with seven ships, he sighted and pursued four French vessels near Santa Marta. Benbow's captains mutinied and he was left without support in his flagship, the Breda. Although his right leg was shattered by Chain-shot, he remained on the quarter-deck until morning when the desertion of his captains, coupled with the disabled condition of his ship, forced him to abandon the chase. He returned to Jamaica where his subordinates were tried and dealt with severely; some were hanged from the masts of their own ships in the harbor of London, without having touched English ground again. Benbow died of his wounds in Kingston on November 4, 1702, and he is buried there.

Band 4: ROUND THE CORNER — Richard Henry Dana, Jr. mentions a dozen or more shanties in his book Two Years Before the Mast (1840). One of those is titled "Round the Corner", and scents to refer to this short-drag shanty.

Band 5: THE GREENLAND WHALE FISHERIES — Of the forecastle songs relating directly to whaling which have survived, this one is probably the most popular, dating back to the 18th century. The character of the captain varies in different versions. Sometimes he grieves more for his drowned sailors than for the lost whale:

Band 6: GO DOWN YOU BLOOD RED ROSES — It is thought that this fine old halyard shanty is of Scottish origin. It is mentioned by Captain R. C. Adams in his book On Board the Rocket (1379) as being sung by the Negro crew of an American ship in mastheading the maintopsail, but it is unquestionably of earlier origin than this mention.

Band 7: THE TURKISH REVELEE (Child 286) — This ballad, commonly called "The Golden Vanity," was known more often to sailors its "Lowlands Low". The song has often been connected with Sir Walter Raleigh because of an old broadside text which mentions him as the deceitful captain. The ballad probably orig. mated about the middle of the 17th century when the Barbary pirates (known as Turks) raided shipping in the English Channel and even looted coastal towns. I learned "The Turkish Revelee" from Horton Barker, one of Virginia's finest traditional singers.

Band 8: BONEY WAS A WARRIOR — This short-drag shanty was a great favorite for "sweating-up" the halyards at the end of a long pull. It was popular on both American and British ships and dates from shortly after Napoleon's death in 1821.

Band 9: LADY FRANKLIN'S LAMENT — In 1845, Sir John Franklin, the Arctic explorer, sailed front England with over two hundred men to discover the Northwest Passage. After meeting a whaling ship near Baffin Land, they vanished without a trace. Lady Franklin was tireless in her efforts to locate her husband. Numerous expeditions were organized and in 1859 an expedition whirls she had organized under Captain McClintock finally discovered in a stone cairn on King Williams land a message stating that the ships had been trapped in ice near Baffin Land, that Franklin had died, and that the rest of the company were making an attempt to go south over the ice. None ever arrived. An Eskimo woman told Captain McClintock that the men fell down and died as they walked. This great mystery of the sea was a natural subject for ballad-makers. The version I sing is from Joseph Faulkner's Eighteen Months On A Greenland Whaler (1878), in which it appears as "The Sailor's Dream." The ballad clearly originated after 1845 and before McClintock's discovery in 1859.

Band 10: SANTY ANNA — This capstan shanty grew out of the Mexican War and the exploits of Santa Anna. It has been remarked that General Taylor rather than Santa Anna should be the hero of the song, but Santa Anna had his victories as well as defeats. Before Taylor forced Santa Anna to retreat on February 23, 1847, Santa Anna had forced him to give ground. Perhaps the song developed out of first reports of the fighting at a time when Santa Anna slid indeed gain the day temporarily.

Notes by PAUL CLAYTON

PAUL CLAYTON was born in the great whaling port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, where his ancestors were whaling captains and seafaring men; his grandfather, trout whose singing he first became interested in traditional songs, outfitted whaling ships for many years. The songs and shanties sung by whalers have been his particular area of study for some time. His research in the old logs and journals of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and Public Library has resulted in original contributions to the folk music field which have received high commendation from folklore scholars. Recently he was invited by the Moby Dick Premiere Committee of Warner Bros. and the City of New Bedford to appear as an entertainer at the various festivities in conjunction with the World Premiere of the motion picture Moby Dick. Included on this record are many of the selections he sang at that time. In addition to having previously recorded a number of long-playing commercial records, Mr. Clayton has also recorded songs traditional in his family for the Archives of tile British Broadcasting corporation, the Flanders Ballad Collection at Middlebury College, Vermont, and for the Library of Congress.