|

|

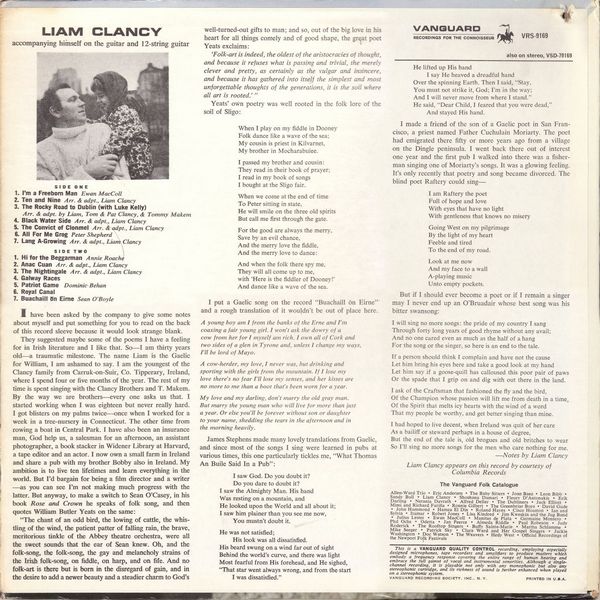

Sleeve Notes

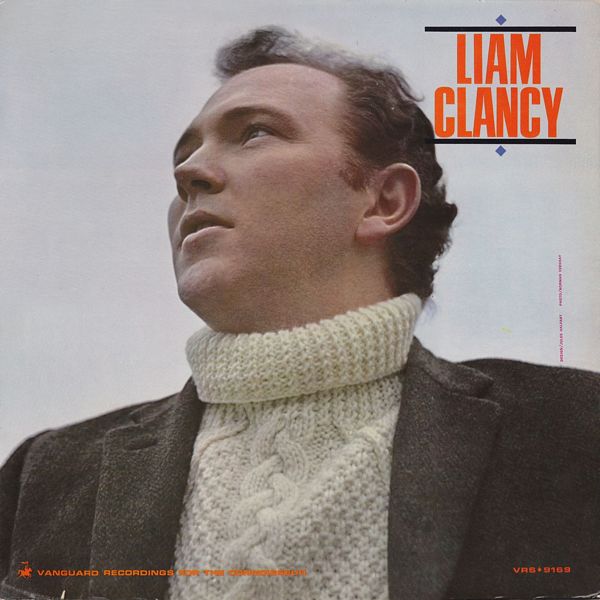

I have been asked by the company to give some notes about myself and put something for you to read on the back of this record sleeve because it would look strange blank.

They suggested maybe some of the poems I have a feeling for in Irish literature and I like that. So — I am thirty years old — a traumatic milestone. The name Liam is the Gaelic for William, I am ashamed to say. I am the youngest of the Clancy family from Carrick-on-Suir, Co. Tipperary, Ireland, where I spend four or five months of the year. The rest of my time is spent singing with the Clancy Brothers and T. Makem. By the way we are brothers — every one asks us that. I started working when I was eighteen but never really hard. I got blisters on my palms twice — once when I worked for a week in a tree-nursery in Connecticut. The other time from rowing a boat in Central Park. I have also been an insurance man, God help us. a salesman for an afternoon, an assistant photographer, a book stacker in Widener Library at Harvard, a tape editor and an actor. I now own a small farm in Ireland and share a pub with my brother Bobby also in Ireland. My ambition is to live ten lifetimes and learn everything in the world. But I'd bargain for being a film director and a writer — as you can see I'm not making much progress with the latter. But anyway, to make a switch to Seán O'Casey, in his book Rose and Crown he speaks of folk song, and then quotes William Butler Yeats on the same:

"The chant of an odd bird, the lowing of cattle, the whistling of the wind, the patient patter of falling rain, the brave, meritorious tinkle of the Abbey theatre orchestra, were all the sweet sounds that the ear of Seán knew. Oh, and the folk-song, the folk-song, the gay and melancholy strains of the Irish folk-song, on fiddle, on harp, and on fife. And no folk-art is there but is born in the disregard of gain, and in the desire to add a newer beauty and a steadier charm to God's well-turned-out gifts to man: and so, out of the big love in his heart for all things comely and of good shape, the great poet Yeats exclaims:

'Folk-art is indeed, the oldest of the aristocracies of thought, and because it refuses what is passing and trivial, the merely clever and pretty, as certainly as the vulgar and insincere, and because it has gathered into itself the simplest and most unforgettable thoughts of the generations, it is the soil where all art is rooted.'"

Yeats' own poetry was well rooted in the folk lore of the soil of Sligo:

When I play on my fiddle in Dooney

Folk dance like a wave of the sea;

My cousin is priest in Kilvarnet,

My brother in Mocharabuiee.

I passed my brother and cousin:

They read in their book of prayer;

I read in my book of songs

I bought at the Sligo fair.

When we come at the end of time

To Peter sitting in state,

He will smile on the three old spirits

But call me first through the gate.

For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance,

And the merry love the fiddle,

And the merry love to dance:

And when the folk there spy me,

They will all come up to me,

with 'Here is the fiddler of Dooney!'

And dance like a wave of the sea.

I put a Gaelic song on the record "Buachaill on Eirne" and a rough translation of it wouldn't be out of place here.

A young boy am I from the banks of the Erne and I'm coaxing a fair young girl. I won't ask the dowry of a cow from her for I myself am rich. I own all of Cork and two sides of a glen in Tyrone and, unless I change my ways, I'll be lord of Mayo.

A cow-herder, my love, 1 never was, but drinking and sporting with the girls from the mountain. If I lose my love there's no fear I'll lose my senses, and her kisses are no more to me than a boot that's been worn for a year.

My love and my darling, don't marry the old gray man. But marry the young man who will live for more than just a year. Or else you'll be forever without son or daughter to your name, shedding the tears in the afternoon and in the morning heavily.

James Stephens made many lovely translations from Gaelic, and since most of the songs I sing were learned in pubs at various times, this one particularly tickles me, "What Thomas An Buile Said In a Pub":

I saw God. Do you doubt it?

Do you dare to doubt it?

I saw the Almighty Man. His hand

Was resting on a mountain, and

He looked upon the World and all about it;

I saw him plainer than you see me now.

You mustn't doubt it.

He was not satisfied;

His look was all dissatisfied.

His beard swung on a wind far out of sight

Behind the world's curve, and there was light

Most fearful from His forehead, and He sighed.

"That star went always wrong, and from the start

I was dissatisfied."

He lifted up His hand

I say He heaved a dreadful hand

Over the spinning Earth. Then I said, "Stay,

You must not strike it, God; I'm in the way;

And I will never move from where I stand."

He said, "Dear Child, I feared that you were dead,"

And stayed His hand.

I made a friend of the son of a Gaelic poet in San Francisco, a priest named Father Cuchulain Moriarty. The poet had emigrated there fifty or more years ago from a village on the Dingle peninsula. I went back there out of interest one year and the first pub I walked into there was a fisherman singing one of Moriarty's songs. It was a glowing feeling. It's only recently that poetry and song became divorced. The blind poet Raftery could sing —

I am Raftery the poet

Full of hope and love

With eyes that have no light

With gentleness that knows no misery

Going West on my pilgrimage

By the light of my heart

Feeble and tired

To the end of my road.

Look at me now

And my face to a wall

A-playing music

Unto empty pockets.

But if I should ever become a poet or if I remain a singer may I never end up an O'Bruadair whose best song was his bitter swansong:

I will sing no more songs: the pride of my country I sang

Through forty long years of good rhyme without any avail;

And no one cared even as much as the half of a hang

For the song or the singer, so here is an end to the tale.

If a person should think I complain and have not the cause

Let him bring his eyes here and take a good look at my hand

Let him say if a goose-quill has calloused this poor pair of paws

Or the spade that I grip on and dig with out there in the land.

I ask of the Craftsman that fashioned the fly and the bird,

Of the Champion whose passion will lift me from death in a time,

Of the Spirit that melts icy hearts with the wind of a word

That my people be worthy, and get better singing than mine.

I had hoped to live decent, when Ireland was quit of her care

As a bailiff or steward perhaps in a house of degree,

But the end of the tale is, old brogues and old britches to wear

So I'll sing no more songs for the men who care nothing for me.