|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

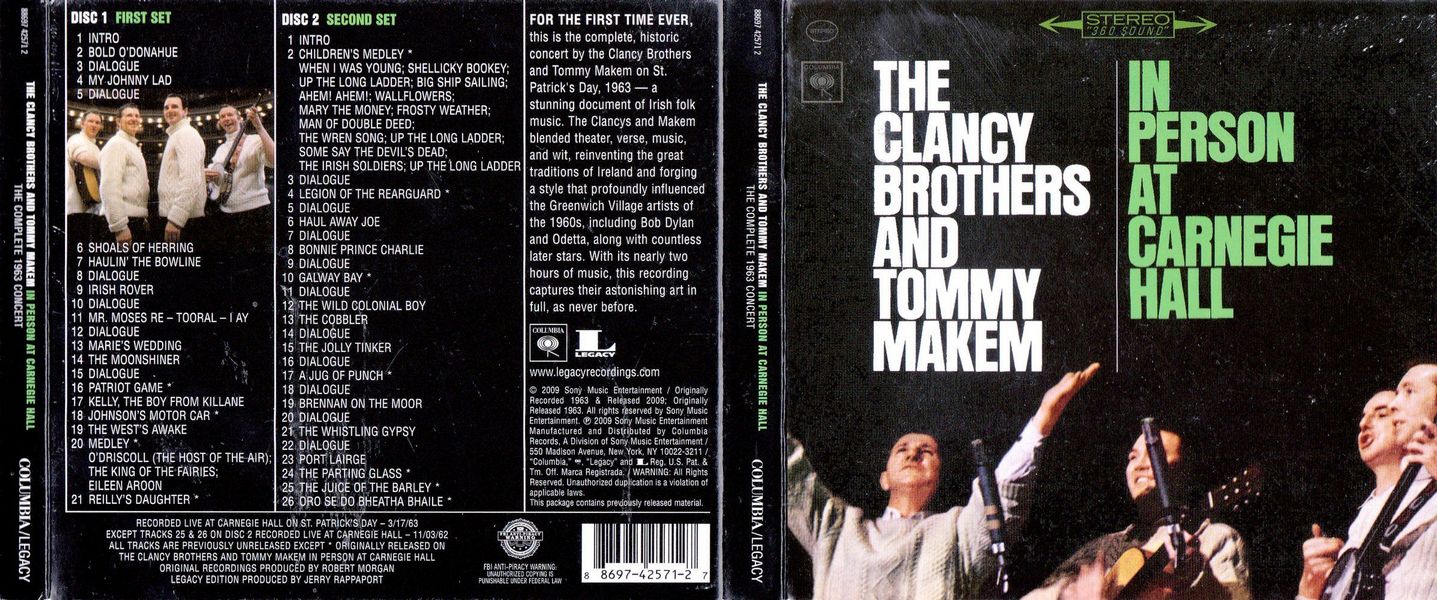

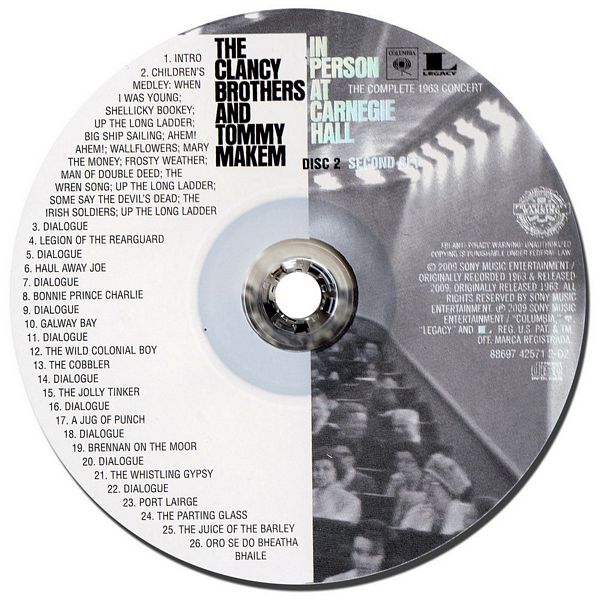

For the first time ever, this the complete, historic concert by the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem on St. Patrick's Day, 1963 — a stunning document of Irish folk music. The Clancys and Makem blended theater, verse, music, and wit, reinventing the great traditions of Ireland and forging a style that profoundly influenced the Greenwich Village artists of the 1960s, including Bob Dylan and Odetta, along with countless later stars. With its nearly two hours of music, this recording captures their astonishing art in full, as never before.

It's been 45 years since I last listened to the March 1963 show. I wasn't ready for the impact it would have on me. The standard procedure when a new album of ours was being released during the Columbia years went like this: the group was given test pressings to listen to and comment on. Then we got the artwork and read (or wrote) the liner notes. When the new baby emerged we played it a few times for family and friends — often embarrassment mixed with pride — and then put it away. It was okay — it was done, dusted and past tense. The next project was all that mattered.

Late last night — two in the morning actually — when the family was asleep — alone in my bedroom, I put on the first disc. For the next hour or so I was back on stage with the lads and the audience who weren't an audience but part of the event, living it, breathing it, seeing it uniquely from within the pack, trading banter and jibes all round. The intros uniquely set the time. Jack Kennedy was in the White House.

"It's not a sin to miss mass on a Sunday any more" Tommy Makem announces, "It's a federal offence! Even the Hail Mary has been rewritten. 'Hail Mary full of grace — the Masons are in second place.'"

Standing in the middle of my room with just the bedside light on I caught sight of an old man in the mirror — it was me. My aloneness hit me hard — hit me hard in the throat — made it lump up. Being the last man standing is no triumph.

How fresh the songs were then — morning bread from the oven — new lamps for old, making their magic. Not yet hackneyed by imitators. They had not been crucified in bars or made to jump, like sick old circus lions, through their hoops — night after night, year after year, fest after paddy-mac-fest.

Perhaps the songs themselves are not as important as the overview of the whole concert — the snapshot of a time and place — the advent of the ability of technology to make a time-capsule of the moment — to not only enable, but to force us, to relive the high points of our lives.

For me, this recording certainly captures a high point.

Liam Clancy

For two hours on a damp Saint Patrick's Day evening in 1963, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem rocked and reeled Carnegie Hall with their saga songs of rebels, outlaws, lovers, and rovers. The performers were well-established stars, though not yet at their peak. The high-spirited audience — consisting mainly, as near as anyone can remember, of Irish-Americans from the New York boroughs and suburbs — overflowed the stalls into seats placed onstage, back behind the spotlights. It would have been easy enough, that evening, to mistake the majestic surroundings for a provincial Irish vaudeville house or even a cavernous pub.

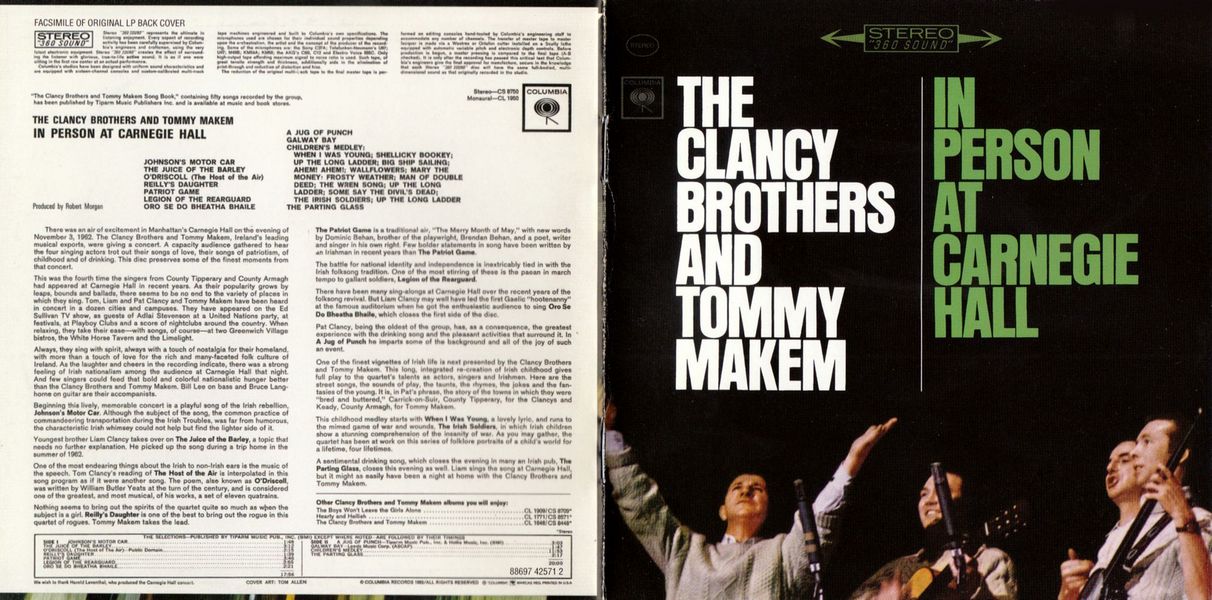

Near the start of the second set, Tom Clancy announced that Columbia Records was recording the proceedings; and later, while introducing a freewheeling version of "Port Lairge," Liam Clancy reminded the customers that, thanks to Columbia, they were all being "immoralize …," no, "immortalized." The concert album, released later in the year as In Person at Carnegie Hall, bolstered the group's growing commercial success in the United States — the record peaked at #60 in the Billboard pop albums chart, a fine showing for an "international" folk act — as well as their following in Ireland, where one-third of all albums sold in 1964 were Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem recordings. Yet for all its charm and popularity, the album did not truly immortalize the concert, and could not, given the conventional recording practices of the time. With only about forty minutes of available space on the entire LP, two-thirds of the songs, including some of the best, had to be dropped. Nearly all of the repartee among the singers, and between the singers and the audience, disappeared. For more mysterious reasons, two of the album's tracks, "The Juice of the Barley" and "Oro Se Do Bheatha Bhaile," came from a Carnegie Hall concert recorded four months earlier. The otherwise informative and evocative liner notes stated that all of the music came from that earlier show.

These alterations may have made little difference to the buying public, but they tore the concert out of its historical context. They also narrowed and jumbled the show's imaginative intentions. Tommy Makem and the Clancys — actors all, and singers in some sense by default — crafted their performances as theatrical as well as musical events, patterned, Liam Clancy recalls, on "the way Eugene O'Neill would construct a play." The original album offered some wonderful excerpts, but the larger work of art was lost.

Now we have it back.

Heard in full, the concert recording dates itself in odd ways, sometimes jarring, sometimes moving. The off-hand references to "Big Bad John in the White House" are the most touching of all. Thoughts of John F. Kennedy and his presidency have long been lacquered in myth and counter-myth, most of it open to debate and reevaluation. But the shroud of tragedy makes it nearly impossible to recall what it felt like to hear Kennedy's name innocently, before the crime in Dallas. It is like trying to inhabit the first or second stanza of a familiar ballad, working up a blissful ignorance about the betrayal or the confusion or the killing that you know is to going to come.

And so it is strange to hear, amid the wordplay, carefree jokes about Kennedy, told with wry Irish exuberance to a packed house of Irish-Americans. More than a century after the Famine migration, the Irish had finally made it in America, and going to hear the Clancys and Makem at the grand Carnegie Hall was one token of that collective success. But having a young, attractive Irish Catholic in the White House was just about the greatest thing in the world. (The musical and political currents had converged six weeks earlier, at the end of January 1963, when the Clancys and Makem performed for the president in Washington as part of a televised awards-dinner tribute.)

After Dallas, an up-from-under barkeeper's son from Hell's Kitchen, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, remarked glumly that he didn't see the point in being Irish "if you don't think the world is going to break your heart eventually." But on Saint Patrick's Day evening, 1963, hearts still beat whole. That these particular four men were leading the festivities, and as singers, was a bit accidental. The elder Clancys, Paddy and Tom, emigrated from Tipperary in 1947 after military service in World War II, living in Toronto before they finally settled in Greenwich Village in 1951. Would-be actors, they quickly found work oh Broadway and on television, and they started their own production company. They sang as well — their mother, Johanna, had taught them some of the old songs at home — but only to help float their production venture, mounting what they called "Midnight Special" Saturday night folk music concerts at the Cherry Lane Theater on little Commerce Street in the west Village.

Liam, more than ten years younger than his brothers, arrived early in 1956, also hungry for acting work — though by then, he had also taken up folk-song collecting and field recording, working with the fabulously wealthy, catalytic, and troubled folklore enthusiast, Diane Guggenheim. During his song recording travels in Ireland with Guggenheim, Liam met and quickly befriended Tommy Makem of County Armagh, another aspiring actor with musical talents and interests. Makem arrived in America one month before Liam, found a job in a New Hampshire mill, and then, after suffering an injury at work, joined the Clancys in New York.

Little by slowly, the music began vying for more attention than the theater — Irish music with a downtown, non-commercial, raffish, and even subversive tone. Prompted by the young folklorist and record producer Kenneth Goldstein, Guggenheim persuaded the Clancys to start up their own record label, and Paddy became the overseer. Tradition Records turned info a wellspring of what became the folk revival, releasing albums by Odetta, Jean Ritchie and Paul Clayton, and Lightnin' Hopkins, as well as Mary Daly, Makem, and the Clancys.

In 1956, Tradition released its fourth LP (and the Clancys' and Makem's first), a collection of Irish rebellion songs called The Rising of the Moon, recorded in Kenny Goldstein's Bronx apartment. The record, and a subsequent album of drinking songs, got noticed by bookers on the pub and folk song circuit as far west as Chicago. From their resident Village stand on still cobble-stoned Hudson Street, the White Horse Tavern — an old longshoreman's bar sanctified as the place where the Welsh damned poet, Dylan Thomas, killed himself by chain drinking his last thirty-six shots of whiskey — the group set off on their musical lark, still convinced it was just an enjoyable diversion from their true vocation.

Their repertoire made no concessions to the syrupy, stage-lrish fare, heavy on "Danny Boy" and "Mother Macree," that dominated mainstream Irish-American musical taste. Neither, though, did they perform in the creepily respectful, drawn-out style preferred by peasant music purists. On the Greenwich Village scene — in places like the Village Gate and Gerde's and the Village Vanguard, as well as the White Horse — they had absorbed the faster rhythms of American folk groups, jazz musicians, raconteurs, and hipster comedians. With their horizons enlarged, they aimed to sing as virile and lusty workingmen, tempered by the tragedy and heartbreak of the ballads. Although they played traditional songs, the Clancys and Makem appropriated and amalgamated freely, creating a musical style that, although unmistakably Irish, was also something the likes of which had never been heard before. And if that wasn't enough to cut them off from the larger precincts of Irish America, they were consorting with the likes of Josh White and Pete Seeger, which meant they must've been "reds" and "nigger-lovers" according to the bigoted, paranoid index that afflicted many Irish-Americans long after the downfall of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Everything changed for the Clancys and Makem in mid-March 1961. They had landed a job performing at the Blue Angel, a swanky supper club on East 55th Street co-owned by the Vanguard's proprietor, Max Gordon. The waiters spoke French, the management wasn't afraid to feature edgy acts — Lenny Bruce played the Blue Angel — and television talent scouts lurked around, including scouts from The Ed Sullivan Show. Having impressed the midtown swells, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem (now the quartet's formal stage name) got booked on Sullivan's live broadcast, and showed up to rehearse on the appointed Sunday — only to be told by Sullivan's frantic production crew that the evening's headliner. Pearl Bailey, wouldn't be making it. Was it at all possible, Sullivan's people asked, for them to work up enough songs to fill the gap?

Even a brief appearance on Sullivan in 1961. with its 80 million viewers from coast to coast, was a godsend for any aspiring entertainer. The quarter-hour slot gifted to the Clancys and Makem made them, instantly, the most famous Irishmen in America. Endorsed by the great Sullivan — Liam Clancy calls it "the blessing of the pope" — they were transfigured from shady Village bohemians into the truest troubadours of the Auld Sod. Their dizzying ascent in show business began. And to the chagrin of the doleful purists and dogmatic non-conformists — the Village Voice called them sellouts, who "weren't as good as they used to be" — their reworking of the songs became the standard of authentic Irish music for the American masses.

(It helped that, just before they landed the Sullivan spot, the Clancys' mother sent over four new, white Aran-knit sweaters to ward off the North American winter's freeze. The group's manager, Marty Erlichman, had been looking for the requisite packaging gimmick for his act, and the sweaters provided just what he needed — a trademark look that had enough of the stage-lrish about it to be safely show biz, but not so much that it seemed ludicrous.)

Around this time, a fidgeting, restless, baby-cheeked newcomer. Bob Dylan, arrived in the Village, listened closely to the Clancys, and hung out with them at the White Horse, young Liam in particular, just six years his senior. Dylan and Liam would pair up at Village parties, Clancy singing "Eileen Aroon" in Dylan's nasal twang, Dylan singing it in what he passed off as an Irish accent. ("Pretty pathetic,” was how Liam recently recalled Dylan's brogue to me. "It was nearly as bad as my Bob Dylan.") The Sullivan show breakthrough had made Makem and the Clancys into exemplars of just how high downtown folksingers could rise without compromising their style. And Dylan's champion, the New York Times critic Robert Shelton, took him to a Clancy Brothers show at Town Hall in New York in late March 1962, in part for pointers on how better to perform on stage.

In 1965, the now renowned but still restless Dylan turned everything upside down at Newport, moving on to become the rock & roll star he'd always wanted to be, but with a new kind of music that the folk purists could not comprehend and hence could not condone. Four years earlier, albeit in a far less dramatic and defiant way, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, unafraid of success, had done something similar with Irish music, then deflected their detractors and reveled in what they had done.

By March 1963, the Clancys' and Makem's world had become a blur. Fueled by adrenaline and whiskey (except for Makem, a lifelong teetotaler), they swashbuckled their way across the popular music landscape. On the strength of the Sullivan appearance, John Hammond brought them to Columbia Records, for whom they recorded thirteen albums and sold millions of records before the decade ended. They performed everywhere and anywhere, from Playboy Clubs to college campuses, capped off by the show for JFK.

Off the road, they sang for themselves and their friends at the White Horse, as well as at the Limelight, just south of Sheridan Square. They toured Ireland, where their reinvention of the old songs, on stage and on the albums, was shaking younger singers out of their slumbers. The writer and television entertainer Shay Healey, then a folk singer, recalls: "It was a sort of performance that we hadn't seen before. It put the joy back into the songs.” For the young Christy Moore, who came up a few years later and helped organize the legendary band, Planxty, the effect changed his life: "I plugged into the Clancy Brothers, got the guitar, and it was a whole different thing."

Yet behind their instruments and beneath their white sweaters, the Clancys and Makem had higher artistic aims, fusing song, drama, poetry, and myth. They had not left theater for folk singing; they brought the theater with them; or, better, they conceived of a concert as a piece of theater.

There was "nothing haphazard" in the group's shows. Liam Clancy affirms. What sounded and looked like their pub bantering or a vaudeville stage pantomime was meant to sound and look that way, partly to evoke the places where many of the songs had originated. But the songs also carried you much further, into the gloaming of Ireland's history and myth. The Clancys and Maken drew directly, sometimes explicitly, sometime subtly, on the Irish masters, especially William Butler Yeats, who had composed his own compounds of myth, song, poetry, and drama half a century earlier.

Five themes appear in the complete 1963 concert recording: love, work, drink, outlawry, and rebellion, set off by two poignant medley pieces. The show opens with the entrance of the bold young Irish lover, just arrived from "Paddy's land," who can seduce any woman, even (or maybe especially) British royalty, with his rolligan and swalligan — sort of a Hibernian equivalent of Muddy Waters' mannish boy. For him, the girls will dance the buckles off their shoes. The visitor is a hard workingman of the sea — a fisherman, who once carried his take to Yeats's Sligo town to be sold — but he is also a universal figure to whom anyone can relate. Galled by British cruelty and stupidity, he takes up the patriot's cause — or might the cause, a song written by Dominic Behan asks, have become a manipulative game? Out of that tension, the show drives deep into the Celtic mists, mingling melancholic fancy, the gay fluted spirits of the faeries, and the lingering strains of passion, constancy, decay, and truth in "Eileen Aroon."

After a rambunctious segue to the intermission, the second set opens with the extraordinary children's medley, pieced together (contrary to the story told at the concert) out of the recordings Diane Guggenheim made in Ireland. Then the show turns into a musicale inside an imaginary pub or, perhaps, beside a hearth, a mix of songs about highwaymen, shrews, and drink that winds down to the quiet benediction of "The Parting Glass." If the concert's first half has been touched by Yeats, the second has a far-away rural village feel, with a touch of the stress as well as the broad comedy of John Millington Synge. The singers seem torn, as if between two lovers — caught up in both the Irish world they left behind and the new world's freedom and excitement. It is much more than a concert of songs by an Aran-sweatered show biz quartet, or any mere musicians.

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem would on to sing for decades, together and apart, and to mount new versions of their musical dramatics. A pair of notable shows at Ulster Hall in Belfast in August 1964, before huge mixed audiences of Catholics and Protestants, infuriated the Protestant incendiary, the Rev. Ian Paisley, and what Liam Clancey recalls as Paisley's "constituency of hatred” — a precursor the Troubles to come. But Northern Ireland is changed utterly now, and the American political musical scenes that helped shape Makem the Clancys belong to a bygone era. When Tommy Makem died in August 2007, Liam Clancy became the original group's sole surviving member.

Despite all that has been altered or lost, though, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem still powerfully influence artists ranging from Dylan and his devotees to Irish singers and songwriters as different as Paul Brady and Shane MacGowan. Their music and its spirit retain an enthusiastic following across the globe. More's the reason to celebrate the full recovery of their art, as they superbly performed it one Saint Patrick's Day evening in Manhattan long ago.

Seán Wilentz

December 2008