|

|

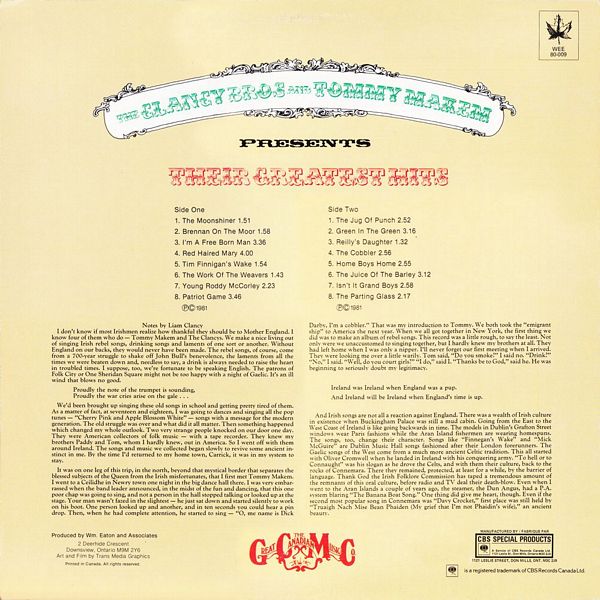

Sleeve Notes

Notes by Liam Clancy

I don't know if most Irishmen realize how thankful they should be to Mother England. I know four of them who do — Tommy Makem and The Clancys. We make a nice living out of singing Irish rebel songs, drinking songs and laments of one sort or another. Without England on our backs, they would never have been made. The rebel songs, of course, come from a 700-year struggle to shake off John Bull's benevolence, the laments from all the times we were beaten down and, needless to say, a drink is always needed to raise the heart in troubled times. I suppose, too, we're fortunate to be speaking English. The patrons of Folk City or One Sheridan Square might not be too happy with a night of Gaelic. It's an ill wind that blows no good.

Proudly the note of the trumpet is sounding,

Proudly the war cries arise on the gale …

We'd been brought up singing these old songs in school and getting pretty tired of them. As a matter of fact, at seventeen and eighteen, I was going to dances and singing all the pop tunes — "Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White" — songs with a message for the modern generation. The old struggle was over and what did it all matter. Then something happened which changed my whole outlook. Two very strange people knocked on our door one day. They were American collectors of folk music — with a tape recorder. They knew my brothers Paddy and Tom, whom I hardly knew, out in America. So I went off with them around Ireland. The songs and music we collected began slowly to revive some ancient instinct in me. By the time I'd returned to my home town, Carrick, it was in my system to stay.

It was on one leg of this trip, in the north, beyond that mystical border that separates the blessed subjects of the Queen from the Irish misfortunates, that I first met Tommy Makem. I went to a Ceilidhe in Newry town one night in the big dance hall there. I was very embarrassed when the band leader announced, in the midst of the fun and dancing, that this one poor chap was going to sing, and not a person in the hall stopped talking or looked up at the stage. Your man wasn't fazed in the slightest — he just sat down and started silently to work on his boot. One person looked up and another, and in ten seconds you could hear a pin drop. Then, when he had complete attention, he started to sing — "O, me name is Dick Darby, I'm a cobbler." That was my introduction to Tommy. We both took the "emigrant ship" to America the next year. When we all got together in New York, the first thing we did was to make an album of rebel songs. This record was a little rough, to say the least. Not only were we unaccustomed to singing together, but I hardly knew my brothers at all. They had left home when I was only a nipper. I'll never forget our first meeting when I arrived. They were looking me over a little warily. Tom said. "Do You smoke?" I said no. "Drink?" "No," I said. "Well, do you court girls?" "I do," said I. "Thanks be to God," said he. He was beginning to seriously doubt my legitimacy.

Ireland was Ireland when England was a pup

And Ireland will be Ireland when England's time is up.

Irish songs are not all a reaction against England. There was a wealth of Irish culture in existence when Buckingham Palace was still a mud cabin. Going from the East to the West Coast of Ireland is like going backwards in time. The models in Dublin's Grafton Street windows wear Paris fashions while the Aran Island fishermen are wearing homespuns. The songs, too, change their character. Songs like "Finnegan's Wake" and "Mick McGuire" are Dublin Music Hall songs fashioned after their London forerunners. The Gaelic songs of the West come from a much more ancient Celtic tradition. This all started with Oliver Cromwell when he landed in Ireland with his conquering army. "To hell or to Connaught" was his slogan as he drove the Celts, and with them their culture, back to the rocks of Connemara. There they remained, protected, at least for a while, by the barrier of language. Thank God the Irish Folklore Commission has taped a tremendous amount of the remnants of this oral culture, before radio and TV deal their death-blow. Even when I went to the Aran Islands a couple of years ago, the steamer, the Dun Angus, had a P.A. system blaring "The Banana Boat Song." One thing did give me heart, though. Even if the second most popular song in Connemara was "Davy Crockett," first place was still held by, "Truaigh Nach Mise Bean Phaidin (My grief that I'm not Phaidin's wife)," an ancient beauty.