|

|

|

| more images |

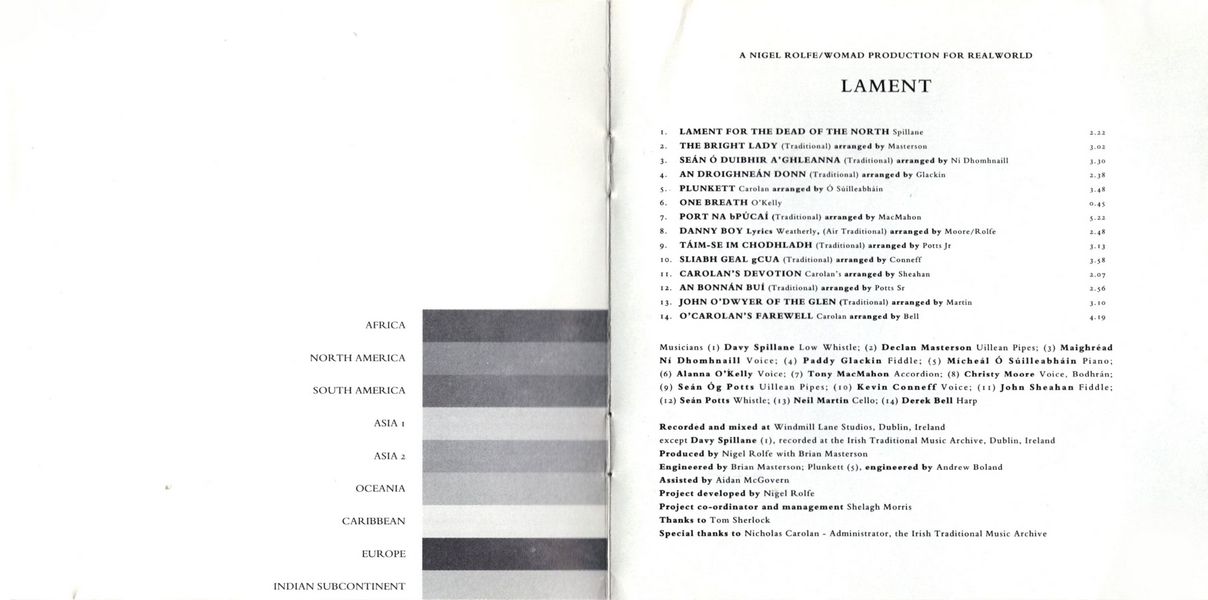

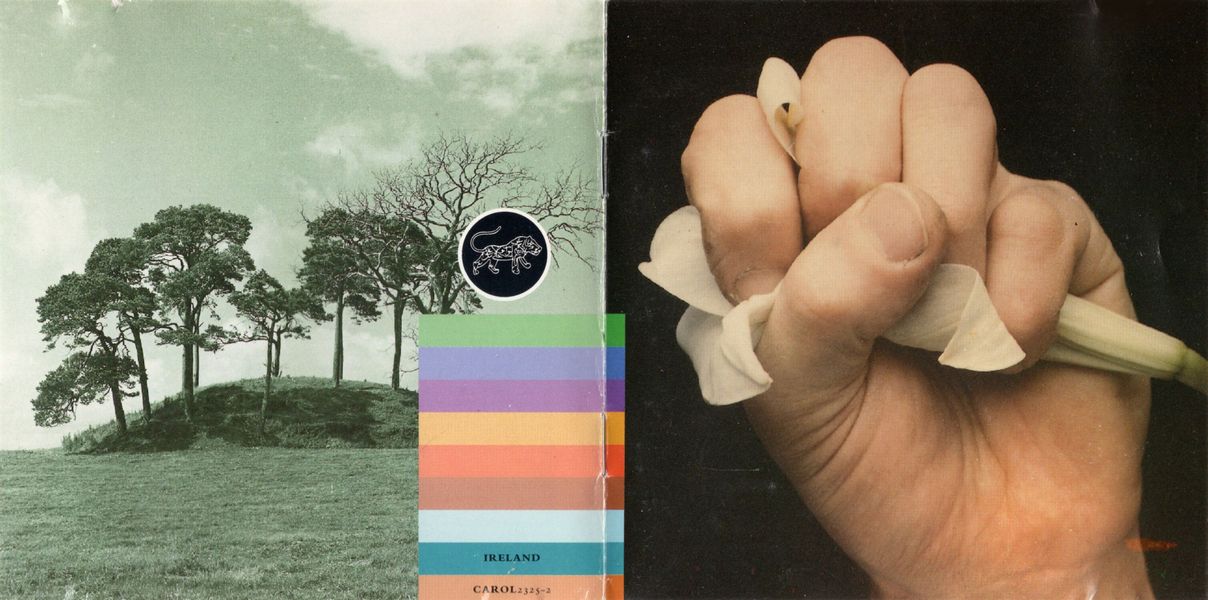

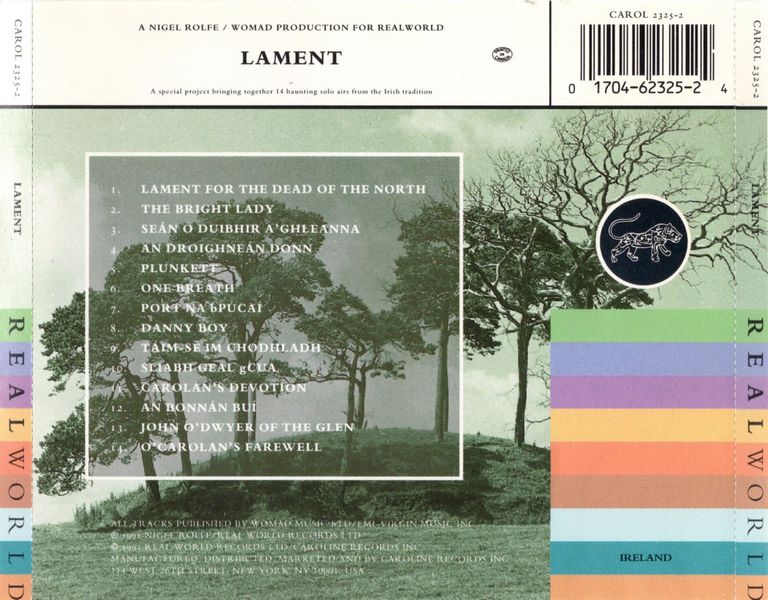

Sleeve Notes

Lament was first conceived several years ago as an event for Derry in Northern Ireland rather than a disc or tape, but no structure for its realisation lived up to the first idea of hair-raising sound carrying across the river at dusk and dawn, hanging in the air and in the mind. Lament was a marker for the power of symbols, of wholeness in a context of fragmentation. The project was intended by Nigel Rolfe as a donation to the city and its people with which he had developed an empathy over the years through a whole series of performance and installation works.

The city of Derry has two names, two opposing claims to its history, two cathedrals, two newpapers and is divided physically and symbolically in two by the River Foyle. The dualities are ever present. The ordinary and the extraordinary. It is a European city — more for its problematic inheritance from the politics of 17th century European monarchies than for its architecture.

"Urban aesthetics is not a question of beauty or ugliness … but of meanings" (G.C. Argon)

This territory of allegiances, signs, symbols and meaning was mapped out in the late 17th century and it is the territory we inhabit now. Until very recently it was the only location in Europe where these earlier forces, founded on allegiance and identity, were crystallised and remained unsettled. Crystallised in the bricks and mortar of the city walls, the housing estates of the Bogside, the border topography stretching into Donegal, social and political systems nourished by those forces and which nourish them in turn. The past is present therefore in Derry and there is no such thing as history in this context. Those forces which underlie any state, long concealed elsewhere in these islands, are visible here. The skin has been peeled back, the nervous system exposed and damaged. It is only now when culture is understood to be fundamental, and in that sense more important than politics, that the damage has been slowly healed in the only way that it can — through the possibility of a new inclusive and legible culture. It’s potential lies in its modesty and in its questioning of the authority of individual authorship. Communications shared, rather than self expression.

Lament is universally legible in that sense because loss is felt not described. These are the cadences of loss and they demonstrate not only the necessity but also the possibility of a new art, a new morality. After lament, optimism is the only choice.

Declan McGonagle

Declan McGonagle is currently Director of the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin.

Irish Music Of Lamentation

Sorrow and joy are the bedrock emotions, according to the classification of early Irish mythology, and each is expressed and induced by its own music: goltraí or sorrow-mode and geantraí or joy-mode. All else is sleep and oblivion. Uaithne, the magic-capable harper of the ancestral Daghdha or Good God, it the earliest musician in Ireland recorded as an exponent of goltraí; Sepainn golltraighi doib congolsad amna dearácha, — ‘He played them the goltraí until their women cried tears.'

In modern reality, the mid-twentieth century has seen the demise in Ireland of a form of pre-Christian lamentation for the dead called "keening", a partly improvised mixture of solo and chorus singing which was an intimate part of ancient death rituals, and the musical features of which link it with the Mediterranean countries and other parts of Europe. Its melodies are typically narrow-compass, melodically and rhythmically free variations on a descending theme of five notes. This theme is also found in the music of poetic elegies in Irish and in instrumental lamentations by harpers, and seems to have been widely used as a symbol of sorrow.

Other types of music of lamentation have been common in the Irish tradition, and in instrumental and in vocal music of all types, the string of sorrow has been often sounded: from conventional expressions of grief for the loss of a deceased lord, a patron or a noble house, to more felt outpourings for the extinction of Gaelic culture, defeat in battle, unhappiness in love, exiled friends, dead wives and husbands, dead children.

The musical expression of sorrow is something which seems to answer as much to some quality in Irish character as to the external circumstances of our history. But there is no music for the greatest disaster to have befallen modern Ireland, The Great Famine of the 1840s. Is silence the music of the deepest sorrow?

Nicholas Carolan, Irish Traditional Music Archive

When Nigel first spoke to me about his desire to commemorate in music the dead of the violence in Northern Ireland, I remember my initial reaction was that this was a subject whose treatment must be so pure in conception and expression as not to fall into the trap of being maudlin or unnecessarily sentimental and indulgent.

Great music has the power to lay bare the soul and arouse in the listener great depths of feeling, and in the Irish tradition the lament has evolved as a music that speaks of sadness and of loss. It seemed therefore to be the music that could express the very essence of the tragedy that occurs daily in our land.

However great music needs great musicians to realise it, and on these recordings we are honoured by the special talents of some of the most sensitive and accomplished artists in the field. That they played and sang from the heart is without doubt. I saw them and heard them and was affected by them.

A decision taken at the outset was to present the music in its purest unadorned form with no accompaniment and without resort to any forms of "studio techniques." As well as being faithful to the tradition I feel that the impact of the music is thus enhanced and its intent is made clear and unambiguous.

I also believe that music can heal and mend, and can save the soul. My greatest hope is that this music might soften the bitterness which exists in the hearts of those who feel that they can only express by violence what is within them, and that it might bring comfort to the friends of those who are gone. And to those who have not been affected by the situation — that it may enable them to feel the pain.

Brian Masterson

The Irish psyche is exposed and informed by music. Time is marked, a nerve is touched, events are noted, spiritual moments recorded, put by as sound in air. It is important to make a tribute, a marker to the sad and unnecessary loss of life through violence in the troubles in these islands. This gathering of laments is a monument to this sadness, to innocence, to hope. Whilst listening there is reflection of a landscape, of a human condition and of profound grief. The situation of innocent death served by others for political gain happens nearly daily in Ireland.

Each musician here was asked to consider this loss of life in the troubles and to reflect it by contributing an air for this anthology.

I have been touched and deeply moved by their spirit and love.

Nigel Rolfe

Irish Traditional Music is of a living popular tradition, it is oral music handed down from one generation to the next, or passed from one performer to another. Much of the repertory is known to have been current in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some is earlier in origin, and it is likely that very old melodies have been adapted to modern forms. Solo performance is at the heart of the tradition and singing is normally unaccompanied.

Although all instruments used in traditional music are not represented, certainly the most important ones are. Some simple notes may be useful. Firstly, a slow sad song/piece in the Irish tradition is an air. Acapella style singing is known as Sean-nós. A song for the dead is a keen, or keening, a lost tradition. The bodhran is a goat-skin drum; the fiddle is not a violin; the uillean pipes are bag pipes, driven by bellows charged by the elbow and not by breath.

This grouping of musicians and singers was brought together not in an academic way but quite organically. They were not asked from a professional reputation but in human terms, although many present here arc the most outstanding players of their kind both old and young, from North and South, famous and less well-known. Particular to each player was that each piece was delivered solo and as the project established, we held to this. It seemed necessary not only for the nature of Lament, but to the way each person found their material, free, hung in the air hut alone.

The youngest player here is Seán óg Potts on the Uillean pipes whose father Seán Potts, a founder of the Chieftains, plays the tin whistle. Both Kevin Conneff, a Sean-nós singer and Derek Bell, Ireland's pre-eminent harpist are current members of the Chieftains. The Dubliners' John Sheahan plays fiddle here as does Paddy Glackin. Alanna O Kelly is a young visual artist who makes a contemporary keen. Christy Moore is Ireland's best known ballad singer. Tony MacMahon initiated this style of slow air playing on the accordion, and Davy Spillane extemporises on the low whistle in a development of traditional material with a contemporary approach. Similarly Micheál Ó Súilleabhain has produced a unique catalogue but contributes a Carolan piano piece here. Maighréad Ní Dhomhnaill is from a strong musical family in Donegal and delivers an air in Irish. Declan Masterson from Dublin plays the Uillean pipes and unusually in the Irish tradition Neil Martin from Belfast plays the cello.